Lead Up International is an organisation that runs programs with a mission to ‘bridge divides and break cycles of violence and poverty’ in Guatemala, the USA, Brazil, the UK, South Africa, Ireland, Austria, Uruguay and Germany. Poppy Woods met co-founder and Guatemala project leader Katie Cunningham Pokorny and four inspiring young people who have been a part of the program at the Ebony Horse Club to discuss the universality of cycles of violence and poverty and how Lead Up’s unique approach to creative empowerment can have a huge impact on helping underprivileged young people to feel empowered to break out of these cycles and fulfil their potential.

As we sit down in the middle of a paddock in the shadows of Loughborough estate and the Angell Estate just beyond it, Lead Up’s co-founder asks us all to take a few minutes to take in our surroundings. I am struck by the contrast of the towering estates on one side, the horses and nature that surrounds us and the sirens as they get lost in the wind. I have come here today to meet four of the Lead Up ‘Champions’, all of whom have lost loved ones to violence and who, after going through the program, are now forging their own paths of advocacy and creative empowerment for others stuck in the same cycles as they were. Awareness, Kate says, is the greatest agent for transformation (to paraphrase Eckhardt Tolle).

The horses, here and in Lead Up programs across the world, are the first step to this awareness, as Kate says: ‘They teach us to perceive everything, and [they] perceive us and read and manage and then help us express ourselves in a more composed way, with a response, rather than a reaction.’

Kate planned this trip after a series of events in Guatemala led her to realise that they needed to act urgently to break the cycle of violence ubiquitous in the country, with their efforts focused on Lead Up champion Denilson Larios (pictured above). Denilson, a 25 year old from Jotenago in Guatemala, tells me his family are one of the known gang families in the area and that he had been working on developing a community arts project as an alternative expression to that way of life. In January one of his fellow Lead Up champions was killed, followed by his brother a few months later, both gang related killings.

After his brother’s murder, Denilson says things became very dangerous for him – a rule of silence meant that he could not report it to the police, and rival gangs had begun circling the home he shared with his family and threatening him. Denilson says that it was the skills he had developed in Lead Up, of self-awareness and emotional intelligence that allowed him to remain calm and it was this that saved him and his family’s lives. Things became so bad that they had to go into hiding – Denilson tells me it would have been easy at this point to ‘make a call’ and carry out the retaliation that was expected of him. All of the Lead Up champions I speak to agree that it is universally known amongst communities with large gang populations, from Brixton to Colombia, that when someone is killed you must retaliate by killing another in turn.

Denilson, however, chose the more difficult route. One that entailed breaking the cycle, instead putting his energy into creative empowerment and a non-violent response which gave back to the community rather than taking more lives. His incredibly brave decision to make positive change in his community, rather than leaving after only 4 of the 60 friends he grew up with remained (the rest having been killed, incarcerated or sent to rehabilitation centres,) reflects his deep believe in the beauty he knew existed at the heart of the community. He was inspired by the time he had spent with another Lead Up champion and mentor, Chota, and after seeing the incredible difference he had made in his community, Denilson wanted to do the same in Guatemala.

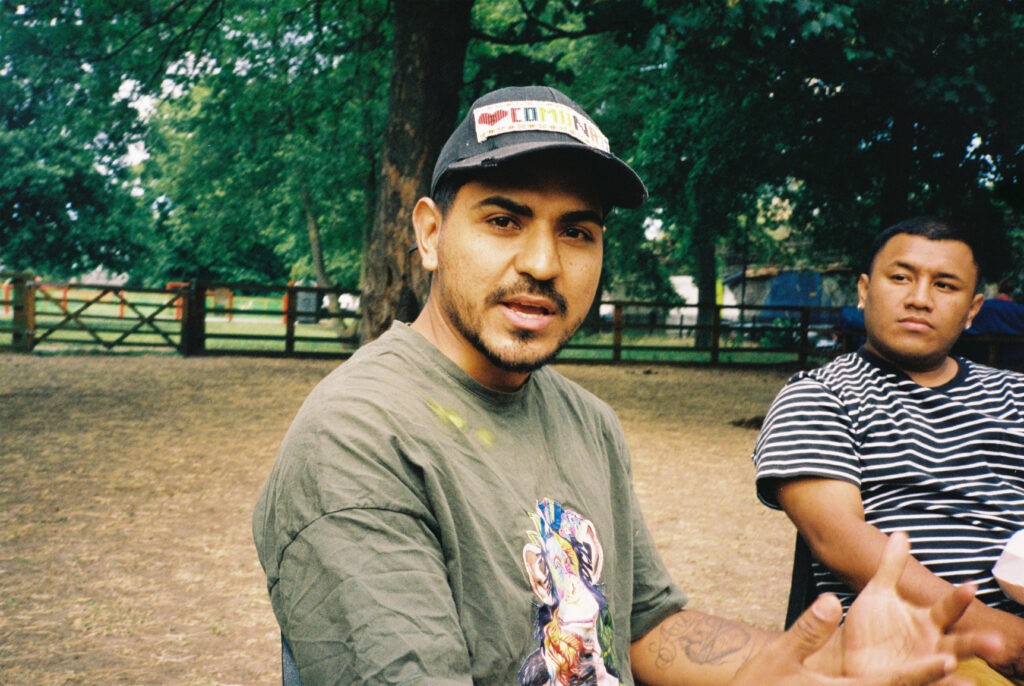

John Serna, aka ‘Chota’ (pictured above), a 33 year old from Colombia, began his own project under the same motivations as Denilson and is now a renowned muralist primarily working on campaigns to promote a community empowerment approach to poverty and violence. Chota tells me that he grew up in Comuna 13, Medellin, once labeled one of the world’s most dangerous communities due to its rates of homicide and its proximity to the main highway (making it the perfect epicentre for the transportation of arms, drugs and money by paramilitary, guerrilla and gangs,) further compounded by the displacement and disappearance of thousands of residents after a targeted initiative by the Colombian military and government to ‘clean it up’.

Chota says that while he was growing up he was always encouraged and expected to join one gang or another, but instead decided to focus on the arts with a group of friends, transforming grey areas that people felt were too dangerous to transit through – he now lives through his painting. He tells me what was most important was to approach the project with the trust of the community, particularly after the failed attempts of the Government to regenerate the area (culminating in Operation Orion.) From the start, he made sure to include his community’s elders’ storytelling and leadership as a part of the creative process, offering the entire community a creative platform for healing and ensuring the murals were seen as respectful works of art as opposed to vandalism.

Chota has played a vital role in the reinvention of his neighbourhood, and now, as well as continuing his incredible work at home, travels to share with others how to start their own creative collectives to break the cycle of poverty and violence. His main advise is inclusion: he says that in order to empower people they must feel a sense of ownership, over a project, a place and themselves. He emphasises the importance of not just getting the elders involved but also the children from the start of the process. On this visit to London he has already been to paint in one of the estates in Vauxhall with the ‘Anticonquista’ and the ‘UK Latin Community’, where he asked the children from the estate from the start what they wanted the piece to express.

What Chota has achieved is amazing and, while he remains far too modest to say it himself, Kate tells me: ‘His community used to be the most dangerous in Latin America. Now you have 10-12,000 people arriving on any given Sunday. So in a month, you’ve got tens, if not hundreds of thousands of people coming to visit this community, thats to this guy and his friends.’

This is something that both Jhemar Jonas, 21, and Million Binyam (pictured above), 22, want to achieve in Brixton. Jhemar, who grew up on one of the most dangerous estates in Brixton says that he is ‘now trying to flip everything’ as well as working on what looks about to become a very successful music career (watch this space), he is also a youth worker, inspiring younger members of the community to also break the cycle.

Jhemar says for him it all started at Ebony Horse Club ‘It was one of those life-changing experiences I can’t really explain. Once you’ve connected to something that big, it changes your perspective on life in general. Even for an individual like myself, violence is what a lot of the young kids grew up learning as second nature: “if the way I approach it don’ work, man’s going to shoot somebody or stab somebody” and that’s a lot of youth’s norms. But my thing was like: “alright, if I can communicate with an animal three times the size of me without having to use any force, why can’t I do that with human beings?’

When I ask him what changes he’s seen to Brixton over his lifetime he tells me: ‘you can see transformation, but not the right type of transformation. For example, now a lot of the youths that were here before have been shipped out to different places.’ He goes on to speak of how instead of dealing with the factors that cause people to be born into negative cycles or find ways and invest in resources to help them find ways to leave, they are often banned from Lambeth, particularly if what they have been charged with is gang related. Million agrees that this is a very popular technique deployed by Lambeth to try and reduce rates of crime, but as Jhemar says: ‘if they decide they’re going to go over there and continue doing what they were doing before, that’s what’s going to happen.’ He tells me that while this sounds like a deterrent, when a person is so used to that way of life they will almost definitely continue and find even more clients in a fresh place.

The issue, he says, is that ‘they (the council and police charged with these decisions) don’t look at the situation.’ and gives those who are already victims to the system a sense that ‘I’ve been banned from my area because I’m already doing this stuff anyway. It doesn’t really look like anyone else is trying to help me apart from just move me where I’m not going to be a problem.So I’m just going to continue doing what I know until I can buy myself out of the problem.’ The issue of improving Lambeth through segregated gentrification is an unavoidable issue, and one that we return to throughout this conversation.

As Chota has created ownership and empowerment in his community through his projects, for Million and Jhemar, this is something they feel has already been declining over their lifetimes, with less businesses now affordable to the community, a cycle that sees cafes being bought up for gentrification, now no longer owned by, or affordable to the communities that have always been at the heart of Brixton. To Jhemar, who at 21 already seems to understand more than many politicains, the cuts to funding of youth programmes serve no-one in the long term, as NHS spending goes up due to higher rates of violence, not to mention the tragic consequences to families and loved ones.

Despite all of this, Jhemar remains optimistic, he knows from his own youth work the power being seen and listened to can have on young people. He has already had experiences in his work where he has challenged beliefs and given perspective on situations that he believes have saved young peoples lives. What Jmemar, who lost his oldest brother to gang violence, articulated in such a heartbreakingly beautiful way was this:

‘What’s even more interesting is the way people will approach us, people will say “Oh, look at these thugs, blah, blah, blah…” But then I question, where’s the humanity? Where’s the humility in you? And where’s the common sense? Because if we all know that all babies are born pure, how on earth are you going to look at this 40 year old, this 50 year old and say “this thug is blah, blah, blah…” When really and truly, you’ve gone through the same process – you haven’t gone through the same environment and the same setting to grow up – but everyone’s growing up is the same. It’s the same in terms of how you go through different things that make you who you are. What you go through varies depending on where you are and who you are. So for people to start looking at certain kids who may be involved in certain things and start attacking them, it doesn’t really make any sense. It’s like asking, are you not a human too?’