Brixton Blog is grateful to The Bard of Brixton, Alex Wheatle, for allowing us the opportunity to publish this powerful essay that has a direct bearing on current debate and discussion

It was Brixton 1978. I had taken a 109 bus from Brixton Hill to Brixton High Street en route to my social services offices on Herne Hill Road just off Coldharbour Lane. Having recently arrived from a Surrey children’s home, I was relatively fresh to the racial dynamics in Brixton. Casually dressed in trainers, jeans, t-shirt, anorak and a beige-coloured cloth cap, I enjoyed the sound of reggae music blaring out from cars, houses and ‘Brixton suitcases’ as I always did when I was out and about in Brixton. Within the fifteen minutes it took me to reach my destination, two white women had crossed the road to avoid me and another had clutched her handbag so tightly to her chest I’m sure it left an imprint of the maker’s brand on her clothing. If I ventured further afield to the leafy avenues of Dulwich or the wide pavements of Putney, there was a more than even chance that someone would alert the police about my presence. For young, black male Brixtonians, this was a daily occurrence.

It was the same whenever I browsed in shops. The security guard would move stealthily to ensure that he’d always have me or my friends in his vision. He would flex his fingers, shift his eyes and ready himself for a confrontation. The more criminally minded of my bredrens used this racial profiling to their advantage. They dressed down and entered clothing stores in the West End. They purposefully acted suspiciously and readily accepted the unblinkered attention from security as a white accomplice lifted all manner of garments.

Football hooliganism was at its peak in the late 1970s and early 1980s. It was a time when shopkeepers located near to soccer grounds would board up their windows on match days. Local parents instructed their young children to stay indoors. Women were warned to steer clear of the streets. In a weekly ritual, rival supporters clashed in pubs, bars and train stations with crow bars, knuckledusters, bottles and other weapons of choice. Yet the SUS laws, where the police had the powers to arrest an individual if they believed they were about to commit a crime, was never employed against white football supporters en route to a football match. In Brixton, I was once stopped by the police for having an afro comb in my back pocket. According to the arresting officer, it was an offensive weapon and I had behaved menacingly. “What?” I said. “Are you saying I can’t flick out my afro? You gotta be fucking kidding me!”

Inhabiting a black skin was mistrustful enough for them.

These were the days of police intimidation, beatings in cells and forced confessions. No statements or witness accounts were filmed or recorded. I’ve never heard of an account where a black man was assaulted by a single officer whilst in custody – there were always three or more assailants. The mere presence of a black man, perceived by most of white society as wild, violent and sexually dangerous, led to a fear that had to be eradicated.

In 1955, it was this same irrational dread coupled with entrenched racism that led to two white men, Roy Bryant and J.W. Milam, abducting and mutilating the fourteen-year-old black boy, Emmet Till, before shooting him in the head and dropping his body into the Tallahatchie River, Mississippi. The supposed crime that Emmet Till committed was to flirt with Roy Bryant’s white wife, Carolyn.

I have visited Emmet Till’s shrine at the National Museum of African American History in Washington DC. I stood perfectly still as I viewed the original casket Emmet’s body was buried in. Although Emmet’s face was hideously deformed, at his funeral, his mother decided on an open casket so the whole world could witness Emmet’s defacement. I couldn’t help asking myself, ‘what hellish, primal, deep-seated racist fear could cause Bryant and Milam to inflict such appalling injuries on a child?’

A similar trepidation has led to numerous unarmed black men being executed by American policemen. These same officers never seem to be so anxious or trigger-happy when apprehending white murderers who in some instances have slain scores of people. More often than not, they manage to present themselves at court unscarred, unshot and unharmed. The media never labels them terrorists.

Even a silent, still gesture from a black man can terrify fragile white folks.

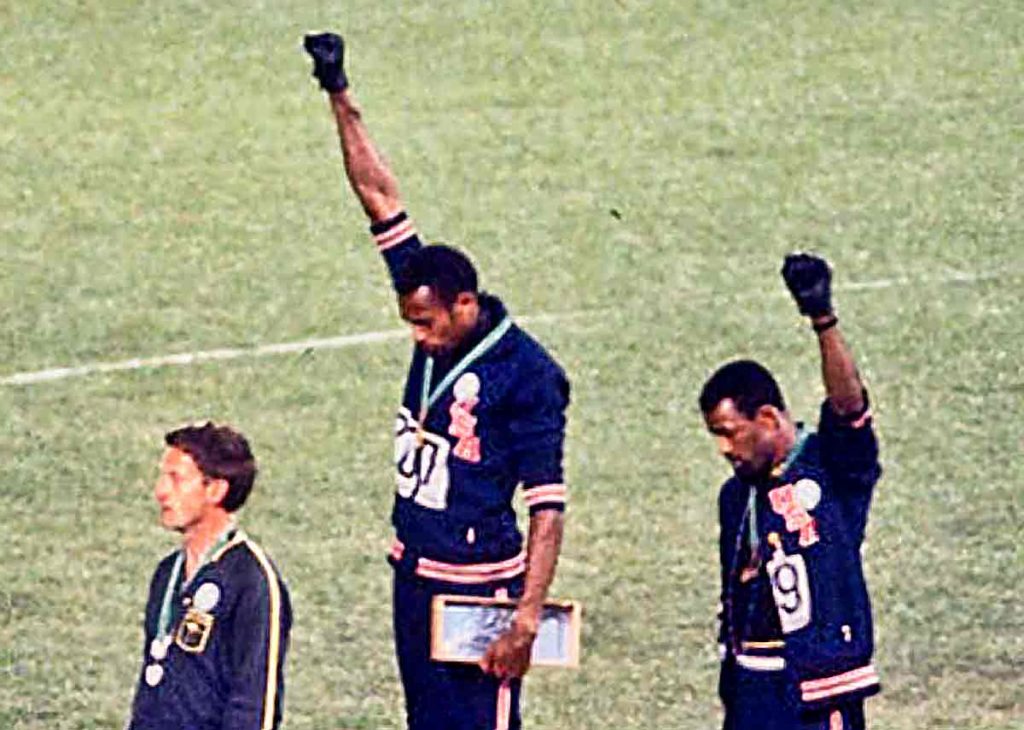

In London, I was fortunate enough to meet one of my boyhood heroes, Tommie Smith, winner of the 200m sprint at the 1968 Olympic Games in Mexico City. In protest against the way Afro-Americans were dehumanised, killed and condemned to poverty in a rabid, racist society, Tommie Smith and his compatriot, John Carlos, marched out shoeless to their medal ceremony in black gloves and black socks. As the US National anthem blared out in the huge stadium, Tommie Smith and John Carlos raised their black-gloved fists in acknowledgement of those who had fought and lost their lives in the struggle. For this act, Mr Avery Brundage, President of the US Olympic Committee, took extreme offence. He immediately suspended Smith and Carlos from the Games and expelled them from the Olympic village. This was the same Avery Brundage who didn’t utter a murmur of dissent amid the mass Nazi saluting at the 1936 Berlin Games.

White America has means of making black men pay for forcing them to face and acknowledge their own atrocities.

Smith and Carlos returned to the US. They struggled financially and initially found it almost impossible to gain meaningful employment. Almost half a century later, Colin Kaepernick, the American footballer, has also discovered that a silent, still gesture, taking a knee as the US National anthem is being played before a game, will destroy his job prospects. As I write, no National Football League franchise has offered him an opportunity to resurrect his career. He was regarded as one of the best quarterbacks of his generation. Oh yes, they’ll always make us pay.

For the black man to be fully accepted, we have to strive to be perfect, compliant and not seen as a threat or an uncomfortable reminder of a genocidal colonial past.

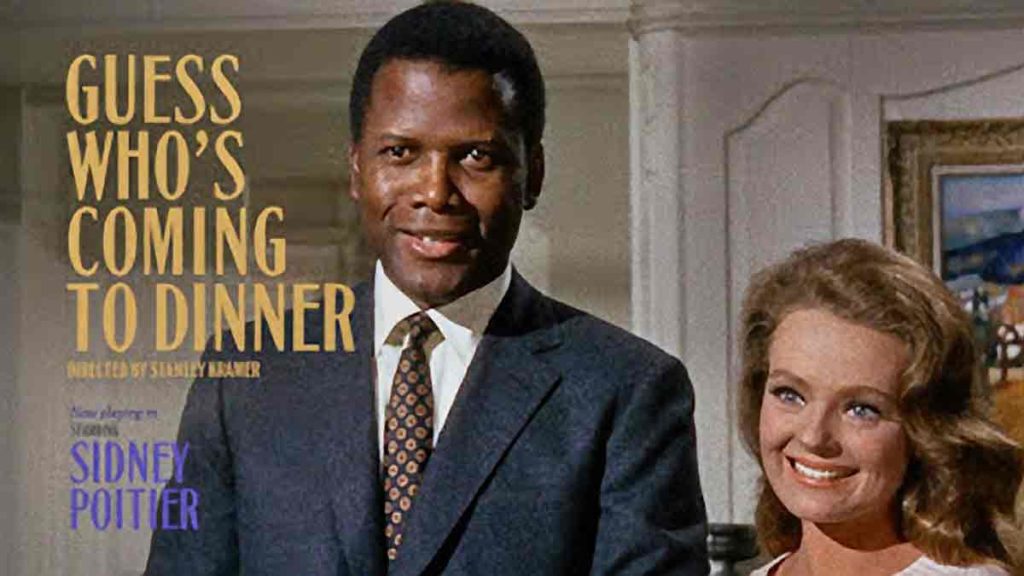

In 1967, Sidney Poitier, the esteemed black actor, starred alongside Spencer Tracy and Katharine Hepburn in the film, Guess Who’s Coming To Dinner, Poitier plays the black fiancé of a young white woman who is presenting him to her parents for the first time. Sidney Poitier’s character, Dr John Wayde Prentice Junior, is an impossibly idealistic man who graduated from a top school, began medical initiatives in Africa, is faultlessly groomed and, wait for it, even refused to partake in premarital sex. I love Sidney Poitier but I detest this movie with a passion because it says to the black man that for white middle class society to accept us, we have in effect, to conduct ourselves like a Godly image only found on the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel.

In 1981, white alarm reached new heights in the UK when black people held their ‘Day of Action’ march protesting against police apathy and inaction following the New Cross Fire where thirteen young black youngsters lost their lives. Thirteen dead, nothing said we chanted. As we crossed Blackfriars Bridge that day, I witnessed at first hand the growing panic and racial taunts from the police even though the rally was peaceful.

In the present day, I have recognised the same fright in white teachers when black male students banter or argue boisterously in school classrooms and corridors. They overreact and escalate the tension in a way they would never do if they were addressing white boys. Black male pupils are much more likely to be excluded from schools than their white counterparts for the same offence. When black men enter the justice system, they are more likely to receive longer sentences than white men for identical crimes. On first glance, black men are perceived as more of a physical threat to society than any other racial group. The statistics don’t lie.

As an award-winning writer, even I’m not immune to a mild sense of apprehension when I’m speaking at high society venues and prestigious book festivals. Recently, I arrived at a prominent literary festival wearing casual clothes (as mostly every other author does) As I walk into the Green Room, I sense suspicious eyes on me, a sudden alertness and stiffening of shoulders. To date, I’ve been asked if I’m in the band. Do I know where the cloakroom is? Am I aware this is the Green Room and only reserved for writers? Where can I get a drink? This space is not for the public and my favourite, are you lost? On all of these occasions, I detected a small dose of trepidation, an over-compensating smile and an obvious relief when I explain that I’m a writer. I try to be as approachable as I possibly can but sometimes the old rebel in me would like to produce my best Brixton scowl.

When I’m going about my daily business, I sense this unease, this fear of a black man. Simply waiting for my turn at an ATM machine can cause anxious glances over shoulders and a hurried look along the street for potential support. I’m confronted by a similar nervousness when I attempt to gain entry late at night into a club or bar. The eyes betray the bouncers’ thoughts – is this black man here to cause trouble?

I have to peel back the years to try and understand this illogical terror.

Slavemasters excused their abominable behaviour towards their black captives by convincing themselves and others that their slaves were animals. From South Carolina, John C. Calhoun, the 7th Vice President of the United States, said in a famous speech in defending slavery, “Never before has the black race of Central Africa, from the dawn of history to the present day, attained a condition so civilised and so improved, not only physically, but morally and intellectually.”

The implication was blatant. According to John C. Calhoun and his fellow slavery apostles, black people were sub-human.

Articles debating the slavery/antislavery issue were published in the Charleston Mercury. Numerous slaveholders strongly believed that “slavery would liberate Africans from their savage-like ways.”

So my ancestors were granted the status as ‘animal’. This rank has seeped into the consciousness of many ignorant white people over many centuries and decades. It’s taught to their children and passed on to their children’s children. Now, the hatred is whipped out and fanned by right wing media commentators, politicians and social media trolls. The 45thPresident of the United States says they are fine people. It always disturbs me when racists believe they have a license to brand us as monkeys, apes and gorillas, something that is inhumane and not quite civilised. I switch over the TV channel when I’m watching a soccer match and I hear monkey chants whenever a black player nears the ball. For me, the insults dredge up the belief that black people need “slavery to liberate Africans from their savage-like ways…” I’m not apologising for repeating this phrase.

The racist abuse perpetuates the myth that we are untamed, wild and dangerous. Hence the wary glances, the tightening of shoulders and the mild tension in the cheeks as I enter a Green Room at an esteemed literary festival.

My spirit informs me that black people carry a sense of injustice in their bloodline (Rastafarian brethren are always instructing me that the blood remembers) I also believe that those who have greatly benefited from our slave state have this subconscious and wholly conscious dread that one day there will come a reckoning when we will exact a merciless revenge. It’s why in the past our freedom fighters were quickly silenced and executed.

There are numerous slave revolts I could mention that occurred in Jamaica but I’ll relate the story of ‘Tacky’, who was born in my mother’s parish of St Mary. In 1760, Tacky and his band killed their slavemasters and took over a nearby fort that contained guns and ammunition. The British sent in reinforcements, more slaves from adjacent plantations joined the rebellion and the battle raged for a number of days. Tacky was hunted down and finally captured. His severed head was displayed on a long pole in Spanish Town to serve as a warning to others. Rather than return to a slave state, many of Tacky’s followers committed suicide in coastal caves. They didn’t teach me tales like this when I was at school.

Over a hundred years later, a similar fate awaited another Jamaican freedom fighter, Paul Bogle, and he wasn’t even a slave. He was a man of the church. That didn’t save him. No chains on my feet but I’m not free, Bob Marley and the Wailers sang in the early 1970s. The Jamaican reggae icon never killed anyone but the CIA kept a file on him because they knew he had the rhetoric, the intelligence and the power to rouse the black masses. To put it simply, they feared him.

To this day, the message to us is clear: if we see you as a threat, if you force us to confront our vile colonial past, if you dare to question our morality, beliefs and self righteousness, if you light the flame of black consciousness and solidarity, we will find ways to silence you, discredit you and eliminate the way you make your living. Muhammad Ali and Colin Kaepernick can bear witness to that.

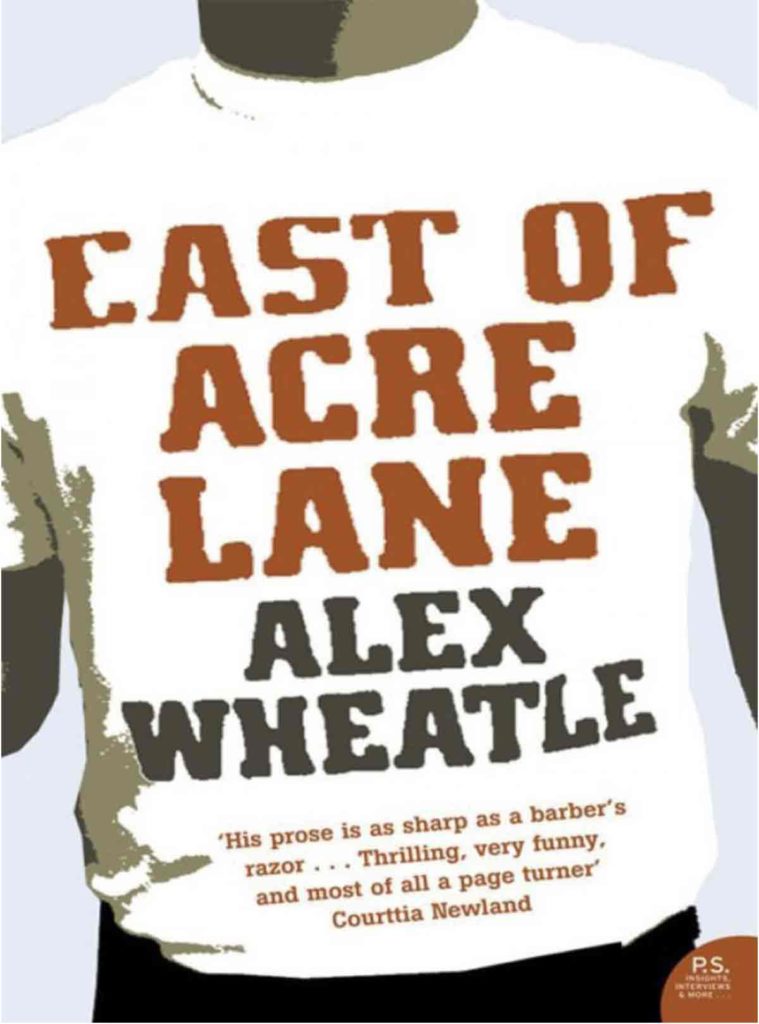

In 2001, I published to what I consider my most important novel, East of Acre Lane. It’s set against the backdrop of the 1981 Brixton uprising and brutal police oppression acting under what I regarded as an inherently racist Conservative government. It was critically acclaimed wherever it was reviewed. If I can indulge in a little head-swell for a moment, here are three of them:

…Treading a Dubliners-esque terrain which swallows up the Brixton landscape, the novel spits out the simmering frustrations of being young, black and British during the Thatcher years…Wheatle retells a shaping episode in recent British history and tellingly captures as much of today’s mood as he does of an unforgettable 1981.

Pride Magazine

…A vibrant and highly evocative insight into one of the most explosive periods in London’s history.

Scotland on Sunday

…Wheatle has written a hard-hitting novel which is an incendiary reminder of one of the most explosive events in London’s post-war history…

Big Issue

After assessing my reviews, please forgive me if expected to be feted at literary festivals, named on shortlists for book prizes, my text to be included as essential reading on the national curriculum and serialisation rights on BBC radio. Yes, I did dream. For a year or two, it was even optioned by the BBC as a potential drama for television. I went to my bed in those days thinking good things. Gosh, how naive was I.

None of the above happened.

I believe I was seen as a threat, a black man who made white people feel uncomfortable by my presence and the words I print on the page. East of Acre Lane was too incendiary. Amidst descriptions of vivid racial violence, it contained depictions of a young black male wanting to kill police officers. I guess I didn’t quite tick the boxes like Dr John Wayde Prentice Junior in Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner. I didn’t graduate from a top school, attended Oxbridge or any other top-ranking university. Alex Wheatle’s an angry, uneducated black man from Brixton who was raised in a children’s home. What true artistic merit can flow from his unschooled pen? It’s better to promote black narrative texts that are palatable to sensitive white tongues.

If we can push my novel aside for a moment and consider why hasn’t one of the most significant events in black British history ever been dramatised for UK terrestrial television?

Since the publication of East of Acre Lane, it’s only through sheer persistence, fierce stubbornness and what talent I possess that I have managed to fashion a career in this old writing game, for so long the domain of white middle-class men. I’m still driven by this overriding urge to write our narrative.

I yearn for the day, when I can walk into an establishment, wearing my casual clothes, my red, gold and green shoulder bag, listen to Dennis Brown on my headphones and not be given a flicker of attention or perceived as the slightest of threats. I don’t think that day will come in my lifetime.

For the unaccountable atrocities that my ancestors had to endure, it is me who should cower in the presence of white men. It is me who should look up and down the street for potential support in case of an unprovoked assault and me who should be mistrustful of a paler skin. But it is me who is still seen as a menace to society.

Fear of a Black Man is taken from SAFE, an anthology on the Black British male experience, edited by Derek Owusu.

Cane Warriors, Alex Wheatle’s latest book, will be published on 1 October