Co Arts Editor Barney Evison sat down with local poet and community figurehead Michael Groce for a long overdue chat. They talked about demon barbers, the Cheltenham Festival and how to put poetry into practice.

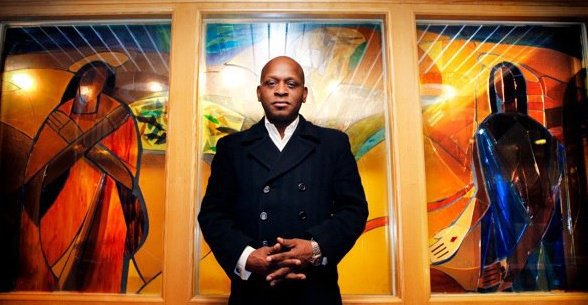

Brixton poet and reformed criminal Michael Groce is a man on a mission.

With his friend and business partner Philip Davies, he is working hard to lift young people out of poverty. His courses – Groce Conduct and Unlock – aim to coach young people from disadvantaged backgrounds and long term dependency on benefits to full-time, sustainable self-employment.

I met Michael and Philip in Lounge on a cold January evening to find out more about what they’re up to.

If the name Michael Groce is familiar to you, it may be for a reason other than his poetry. He is famously the son of Cherry Groce, the Brixton resident who was shot by armed police at her home on Normandy Road in 1985, sparking Brixton’s second major riot.

At the time, Michael was involved in gang crime and drug dealing and the incident which led to his mother’s shooting was a result of police reports that he had a gun at her address. After seeing his mother’s picture on television and learning of the rioting, Michael came out of hiding and turned himself into the police.

It’s hard not to see this as a defining moment for Michael. Does he think he’d still be a poet if his mum hadn’t been shot? “I don’t think so,” he admits. “I’d probably still be on the street, selling drugs.”

He had numerous encounters with the police in his youth, with around 50 separate convictions and 15 spells in prison. The past holds a lot of pain for Michael. His mother, who survived the shooting but was paralysed from the waist down, died in 2011. Her death hit him hard, forcing him to take a year out from his busy life of writing and community work.

Michael Groce is not a man to stay serious for long, and makes Philip and I laugh when recounting stories from his earlier, madder days. He remembers his stint cutting inmates’ hair in Brixton prison. After a change of scene, he asked if he could be the barber but neglected to inform anyone that he’d never cut any hair before. “First guy I cut, I was on the phone with one hand, asking my friend how to do a short back and sides.

I became the demon barber of Brixton prison,” he chuckles, “everyone had a Number 2, the whole jail looked the same!” He wrote a poem based on his experiences in prison, ‘Canteen’: “that was the most used word in prison. Everyone associated it with food, whatever language they spoke – when they heard it they came running!”

Michael turned his back on a life of crime and drug addiction to throw himself into poetry and community work. He’d harboured a desire to write poetry from a young age, inspired by buildings named after poets at the school he attended in Sussex while in residential care. “People told me not to be a poet when I was younger. They told me it was a waste of time.” What drove him to ignore them later in life? “I didn’t want to just be known as ‘that guy whose mum got shot’ or ‘that guy who sparked the riots’ – I wanted to be known for something else.” Recognition initially came in the form of the Cheltenham Poetry Prize, which he won in 1998. He stunned the audience at the festival, getting through to the last round and performing a poem about his mother: “At that point people there suddenly realised who I was, they recognised my familiar name.”

Michael still wants to distance himself from his younger, angrier self: “People have this image that I’m enraged. Now, I don’t enrage, I engage.” As the discussion turns to his community work, I ask whether poetry is still an important part of what he does. “Poetry underpins everything,” he says firmly, “poetry cuts through culture, it’s a common language.” The poem ‘Unlock’ frames the ethos behind the programmes that Michael and Philip run, and his prison poem ‘Canteen’ is the basis for an ex-offenders training programme with the same name. They target young people, often men, who are reliant on benefits and help them set up their own businesses to become self-sufficient. They see self-employment as a way in which people can use state support like tax credits constructively to build themselves a sustainable future.

In their own words, Michael and Philip’s programme “doesn’t go for the low hanging fruit, but wants to harvest those at the top of the tree.” They actively seek out troubled youths, venturing into the darkest corners of Lambeth, places they know where gangs and drug users hang out, squats and street corners. They criticise other community programmes for expecting that people will come to them, as opposed to going out into the community and finding those who need help. Philip is no stranger to troubled inner city areas himself, originally hailing from Moss Side, the infamous Manchester neighbourhood that earnt the city its nineties nickname ‘Gunchester’.

When I ask Michael if policing works in Brixton today, he says there is still a way to go in terms of police presence and accountability. “Policing does work, but they still need to make sure they go into the darker areas.” I ask him if he was surprised by the lawful killing verdict in the Mark Duggan inquest in January. “No. I made the prediction beforehand that it would be lawful killing and my friends wouldn’t believe me. The law has to be like that – it’s there whether we like it or not.”