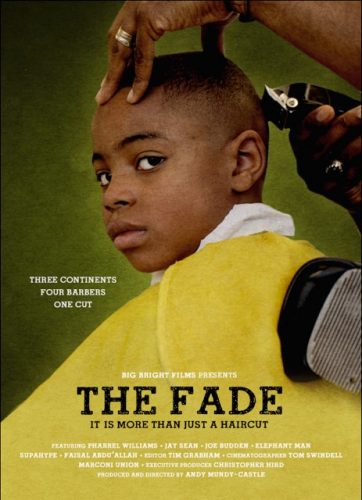

Keith Lewis met with local Film Director Andy Mundy-Castle before watching his superb documentary, The Fade, at the Ritzy.

Andy opened his first feature length documentary, The Fade, with an apology to the Ritzy staff. He grew up a popcorn kernel’s throw from the cinema and confessed to regularly sneaking in without a ticket. He was pleased to be able to give something back, he joked.

Before the screening, I chatted with Andy about his homecoming and the motivations behind the film, based on the narratives of four independent barbers.

Firstly, his brother was once a barber in Brixton. That kicked off his intrigue, naturally. But as a film lover, Andy himself used to own the Apollo video shop in Herne Hill. ‘I was just a young man,’ he said, ‘so I didn’t see what was coming. People were changing their movie-watching habits.’ But he loved the dynamic, the sense of place. ‘I saw kids growing up in that shop,’ he added. But the video shop as we knew it didn’t have much life left in it.

To Andy, his own store was not a million miles away from a barbershop. In his documentary, a high profile client of one of his subjects jokingly refers to the barbershop as the hood twitter. Certainly, suggests Andy, it is where all the interesting conversation goes on. Plus it is cross-generational, he adds. As such it is a rare and precious space.

Andy talks enthusiastically about the first time he visited a barbershop himself. ‘If I think about it, it was my first ever financial transaction,’ he said. I asked him if he had been nervous. ‘Don’t you believe it. All those eyes watching you. You want their respect – the respect of a brotherhood, a male community.’

His film kicks off with a modest introduction to each of the four barbers. They are based in different countries: Ghana, Jamaica, USA and the UK. The locations represent the African transatlantic movement, following a kind of geographical slavery narrative, Andy tells me.

Its scenes are knitted together seamlessly by some up-close, tender cinematography. As a consequence The Fade is humane. Intrigue is built gradually as we begin to see deeper into the lives of each barber. To use Andy’s own words, the film is an injection rather than a bullet.

The Fade skillfully contrasts and binds each subject simultaneously. In Accra, Tupac of Star Hair Cutz admits, “The barber shop has taken me far, wouldn’t have a livelihood otherwise.” As a barber he recognises that he will never go hungry. “But,” he says, “one day I hope to move into music. I don’t have support, but plenty of ambition. And dreams.”

As well as masculinity then, the film covers a human dilemma with a modern global urgency – everyman wants to be something different.

Then it is over to the US. Johnny “Cakes” Castellano inhabits a wholly disassociated and contrasting space from his Ghanaian peer. We follow Johnny as he takes a helicopter flight to NYC to cut DJ Envy’s hair. “I know you got Jay [Z] to cut but you gotta fit my arse in somehow,” says DJ Envy. Johnny is a barber to the stars, you see. And he chases them around New York when he’s not at his New Jersey Barbershop. At the same time we watch him chasing the American dream. Such is the significance of his skills and the demand on his time.

The Jamaican barber, Shawn, is reticent. But his scenes provoked a rapturous reaction, flaunting Jamaica in a beautiful light. Shawn’s own story is adeptly told through his clients, such as the rapper Elephant who relies upon Shawn’s art for his appearance. “A barber keeps your swag up. Even if people don’t know I’m Elephant they gunna know I’m a star thanks to Shawn.” There was much hooting and whooping in reaction. In fact, I cannot recall such an enthusiastic cinema audience in general.

But the film’s fourth barber is who Andy admits to relating to the most. London-based Faisal is an artist as well as a barber. He is a happily metropolitan character who, through his art, spends time around the world. Faisal is happy with the fact that his living comes from this artistic sense of purpose.

But his barbershop is where Faisal’s roots are, where he always returns. The barbershop scenes offer some amusing anecdotal banter and during the film he tells us that it is the force behind his artistic inspiration.

Each of the four narratives is entirely independent. But they feel so honest that, in a way, you have the sense that you are watching a single account of one man – any man for that matter. However, it is the contrast between each barber’s situation that keeps the audience intrigued. You leave one scene wanting to know more about the individual behind it. In the end we are left with a convincing sense of the importance of barbers in society.

It’s a pity that immersive films of this type are difficult to get made as most financers want to assume the audience cannot think for themselves. Thankfully, The Fade spares us that assumption and as such is steeped in honesty and provocation.

Finally, for Andy his film is also about one of the few businesses black people own and support. The considerable majority of people in black communities keep the same barber for years. And Andy makes a strong point that he wanted to show black communities as clean.

‘Have you ever been to a black barber?’ asked the woman in the queue behind me earlier as we had been waiting to get into see the film. I hadn’t, admittedly. But she already knew that. She was ribbing me. And now, post-screening, I was more conscious than I ever have been of my shamefully unkempt mop.

The Fade will next be showing at the Genesis Cinema on Sept 8th as part of the British Urban Film Festival. A general release date of December is expected. Andy’s other work includes David is Dying and Giving up the Weed.