Alan Slingsby reads the shocking story of another epidemic in Lambeth

© Victoria and Albert Museum, London

Boris Johnson, fighting his personal battle with Covid-19 in St Thomas’ hospital in Lambeth, was lying at what had been the centre of another fatal epidemic.

The great history buff might have realised this, but it is unlikely. The victims of this epidemic were not noble Spartans or ancient Athenians, but poor residents of nineteenth century Lambeth, many of them Irish immigrants.

One small memorial plaque records their story in public and what little is known about them is preserved in a few places, including Lambeth archives, but not widely studied or publicised.

Among the victims of that epidemic were members of the Osmotherly family, relations of the six-times great grandmother of Amanda J Thomas, author of The Lambeth Cholera Outbreak of 1848-1849.

Like so many others, they had migrated from the English countryside, Kent in their case, in search of work, finding it in an industrial Lambeth that stretched along the banks of the Thames from Vauxhall to Blackfriars bridge.

© Victoria and Albert Museum, London

That Lambeth has disappeared. A few remnants remain, like the Doulton pottery building at the river end of Black Prince Road and its disused White Hart Dock where the plaque stands.

Older residents of the area remember the pottery that made everything from pipes for the new sewers that saw an end to cholera in London to tea sets. It opened in Vauxhall in 1815 and moved to the Black Prince Road site which closed in the 1970s.

I bought this book a while ago and had not got round to reading it when the coronavirus pandemic made me open it and I’m glad I did.

Cholera epidemics in Britain were common in the nineteenth century and nowhere more than in industrial Lambeth.

Piped drinking water for the local poor was drawn from the Thames near where they lived “down river from the open sewer that was the Effra tributary” – in the words of a report of the time – as well as a lead works and other industries that emptied waste straight into the river.

The water was piped to a Brixton reservoir where it was merely filtered. Brixton prison had one cholera victim during the outbreak.

When, as was often the case, the water did not flow, poor people dipped a pail directly into the river.

Thomas says that at least 2,000 Lambeth residents died in the outbreak.

Her book, no surprise, shows parallels between then and now – the outbreak was foreseen, but no preparations were made; efforts to combat it were woefully under-funded as different authorities bickered; and the cause and the nature of the disease was not fully understood.

Her book, no surprise, shows parallels between then and now – the outbreak was foreseen, but no preparations were made; efforts to combat it were woefully under-funded as different authorities bickered; and the cause and the nature of the disease was not fully understood.

But it is the recounting of the conditions in which poor people lived only a few generations ago that are truly shocking.

Whole families existed in rooms as small as 10 by seven feet.

People kept 10 or more pigs in tiny cellars and few of the thousands of cesspits were connected to inadequate sewers. Human, animal, food and industrial waste lay in heaps all around. Wooden drains running above ground leaked constantly. Built on a marsh, homes were regularly flooded with filth and worse.

When the bone-boiling works were in operation, it was said, no stranger could walk nearby without being forced to vomit because of the stench.

No surprise that many believed cholera was the result of bad air. Some, Florence Nightingale included, never gave up that mistaken belief.

Many people have heard the story of Dr John Snow, the son of a Yorkshire coal yard worker, whose conclusion that cholera was passed on by contaminated water was, in popular mythology, established when he removed the handle from a pump in Soho in another major cholera outbreak in 1854.

© Victoria and Albert Museum, London

In fact, he was already studying cholera and how it was transmitted during the earlier Lambeth outbreak. His work was also mirrored by German and Italian scientists.

This is a scholarly book that concentrates to great effect on a single event, its causes, consequences and victims. Reading it you get a tiny idea of what life must have been like – little changed, if at all, from medieval times. But you have to remind yourself that while people were dying in appalling circumstances in Lambeth, Great Britain was well on its way to becoming the centre of a great empire and the pre-eminent power in Europe.

Passengers on the new railway running to the south west from London passed above scenes of almost unimaginable distress, while its arches filled quickly with the filth and detritus that lay everywhere.

Thomas speculates that the line, which originally terminated at Nine Elms, was extended to Waterloo station so that Queen Victoria, returning by train from her favourite home on the Isle of Wight, did not have to travel by coach through Lambeth to reach Buckingham Palace.

Her book is full of such fascinating observations and facts. Unfortunately, it was published in 2009 by a US-based company and is now only available as a paperback at a very high price.

We are fortunate that, should any other Lambeth resident wish to read it, our excellent local library service will no doubt be able to help them when the current crisis is over.

Photographer who died a pauper

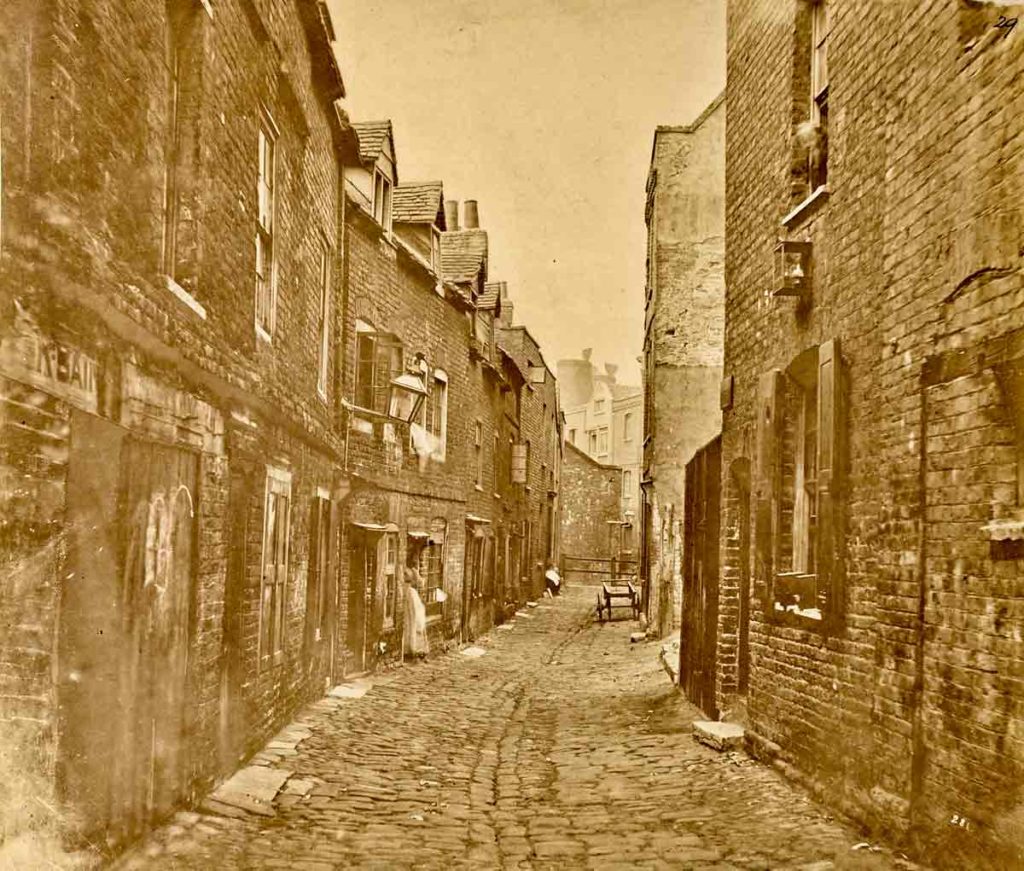

The photographs of Fore Street in Lambeth, were taken in the 1860s, about 20 years after the 1848-9 cholera outbreak, by William Strudwick (1834 – 1910).

A photographic storekeeper at the Victoria and Albert Museum, he also worked as a draftsman, architect, and sculptor, and wrote comic poetry.

Henry Cole, the founding director of the V&A, encouraged the purchase in 1869 of Strudwick’s series of about 50 photographs titled Old London: Views by W. Strudwick.

Lambeth archives acquired a set of Strudwick’s photographs in 1910, the same year that he was admitted as a pauper to Croydon workhouse where he died.

Fore Street and its surroundings were swept away by the construction of the Albert Embankment in 1869. The Victoria embankment on the north side of the Thames, housed a giant new sewer that helped to end cholera in London. The Albert embankment ended flooding in the low-lying areas of Lambeth it protected and also, it was pointed out, greatly improved the view for MPs from their new riverside terrace in the Houses of Parliament, which had burnt down in 1834 and been rebuilt over a long period ending in 1870.

© Victoria and Albert Museum, London

Highly recommend a visit to Crossness Pumping Station, a unique heritage attraction in south-east London. Opened in 1865, Crossness was built by the civil engineer Joseph Bazalagette as part of the first sewer system constructed right across Victorian London. Bazalgette’s new system wiped out cholera from the capital, improved the health of Londoners and enabled our great city to develop and prosper.

You are mitsaken in saying that Florence Nightingale “never” gave up the mistaken belief that “cholera was the result of bad air”. You will find thousands of history books that agree with you, but none written by Nightingal experts (and there are many) since I published my first book on Nightingale in 1998. Even the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography has now accepted that she was a relatively early convert to germ theory.

Hugh Small

Author “Florence Nightingale and Her Real Legacy – a Revolution in Public Health” (Liitle, Brown/Robinson 2017)

Thanks Hugh. I stand corrected.