Thanks to a grant from the Centre for Investigative Journalism, Chrissie Okorie has been working with Brixton Media, publisher of the Brixton Bugle and Brixton Blog, to research the impact of the transatlantic slave trade on Lambeth. This is her initial report

Many of us live on streets and towns with history hidden in between the roads and pavements that we walk on. Some of us live in historic houses owned by prominent people in history who have had a major impact on our lives, whether it’s negative or positive.

Britain has a scandalous history – particularly its involvement in the transatlantic slave trade.

Wealth generated during the slave trade shaped the development of Britain as we know it today, leading Britain to become a world power and trading centre.

Ports across Britain were used to import tobacco, cotton, sugar and rum and to export goods to colonies. Many slave owners became bankers and commercial companies were created from the profits from the slave trade. Banks including Natwest and Barclays have links to slavery.

To trace Lambeth connections to slavery, we need to start with the City of London, home to the Bank of England. It, and the Houses of Parliament, were two key institutions playing a vital role in shaping Britain as we know it.

Brixton was an agricultural hamlet at the start of Britain’s involvement in the transatlantic slave trade, but Clapham was a home to well-off people, many with links to the trade.

Many of the Clapham residents involved in slavery – and the campaigns to abolish of slavery – spent their days in Parliament as MPs or at the London docks as merchants, from where more than one ship a week left on voyages to Africa. To this day you can still see key signs of London’s involvement in slave trade embedded in historic buildings. A good example would be the London Stock Exchange which has images of an African man bowing down to a European.

The death of George Floyd and the re-emergence of Black Lives Matter UK helped to facilitate the conversation about the legacy of the British slave trade.

Many people are now urging the government and local authorities to rename streets and get rid of monuments that honour and glorify slave traders and merchants.

Lambeth council has had conversations about changing street names and statues that were named after local slave owners.

The area has a high population of residents with Caribbean and African roots, who have had to spend years looking at monuments and living on streets named after traders who inflicted pain, torture and trauma on their ancestors.

Councillor Sonia Winifred organised a meeting to hear the thoughts and feelings of Lambeth residents on changing street names with slavery connections.

As a borough, Lambeth was home to more than 20 slave owners and merchants. Many were members of the House of Commons or House of Lords, exercising huge power in government and making arguments on the benefit of the slave trade for the UK economy.

While the whole borough was home to many aristocratic men and women, Clapham stood out the most in this research on Lambeth’s connections to slavery.

Clapham is famously known as the home of the Clapham Sect – a group of abolitionists – and this has been a source of pride.

Abolitionists like William Wilberforce, Henry Thornton, and James Thornton fought in parliament to end Britain’s involvement with slavery.

Supporting them, the Clapham Sect was a group of wealthy evangelical Christians, brought together by John Venn. He was rector of Holy Trinity church in Clapham.

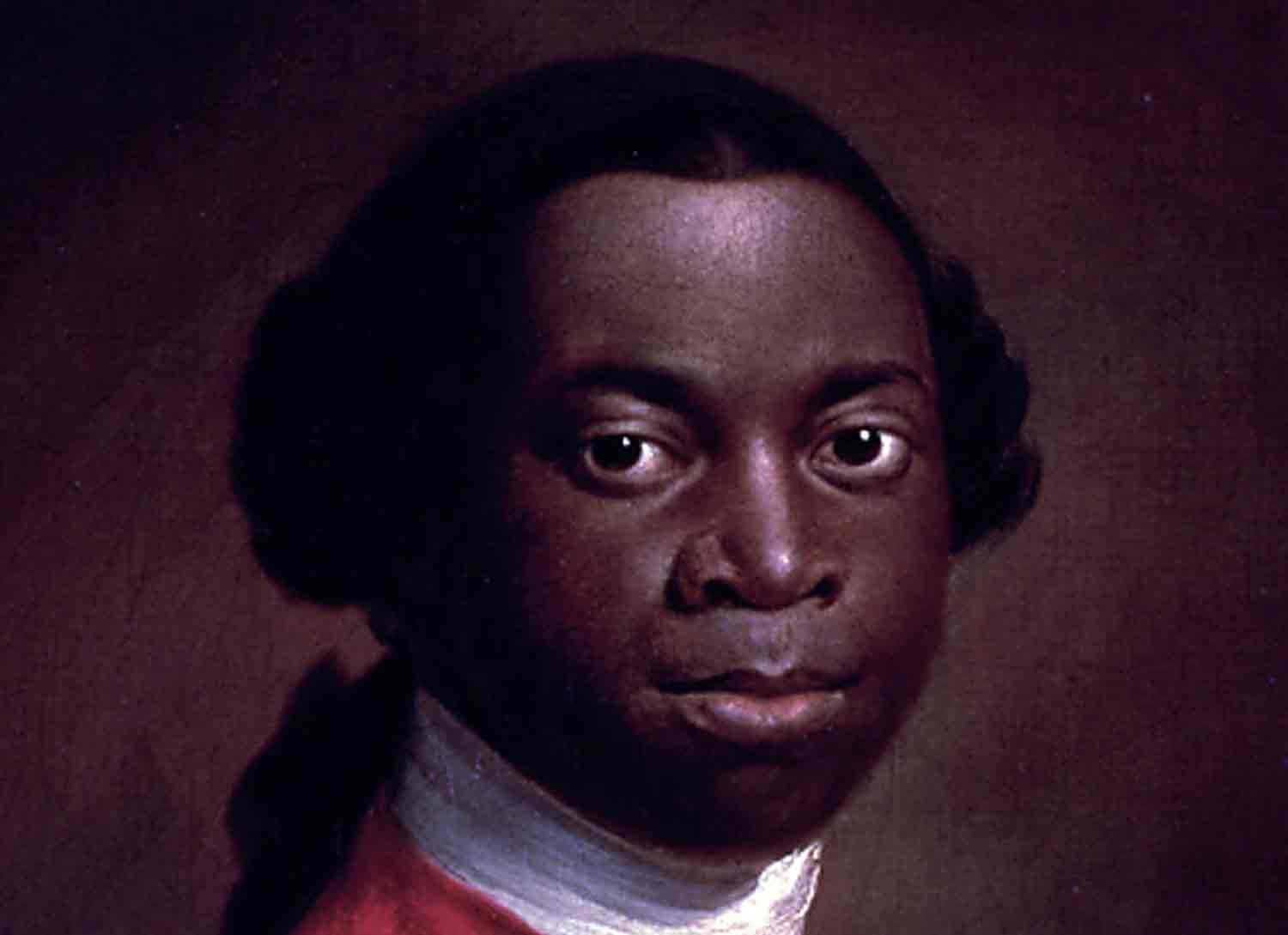

Olaudah Equiano, a former slave and abolitionist was also known to have been associated with the Clapham Sect and was once a Clapham resident as well.

His hard work and involvement in ending slavery is often overlooked in official narratives, which focus on figures such as Wilberforce. But that is a story for another day.

The legacy of the Clapham Sect lives on hundreds of years later. With a blue plaque outside the church to honour its work and many of the individuals involved, including Venn, having schools and roads named after them.

However, beneath the glory and activism, the town holds a deep secret that many people may not be aware of.

Clapham was also home to many slave owners and traders.

Lambeth’s connection to slavery starts in the heart of Clapham. From around 1630, affluent merchants purchased homes in Clapham, moving there from port cities.

Two Clapham residents, John Brett and Richard Cranley, helped to start the slave trade in the UK. They traded tobacco and other goods with their neighbours.

It has been said that their neighbour Anthony Tournay supplied the bilboes (leg irons) used to shackle slaves on the middle passage from Africa to the Americas.

Through the 18th and 19th centuries, Clapham as a town benefited from the slave trade and many of its resident merchants campaigned against the Clapham Sect in parliament.

While the Holy Trinity is known as the church that helped to end slavery, many of Clapham’s slave owners, such as George Hibbert, were members of its congregation.

According to the University College London Legacies of British Slavery database (ucl.ac.uk/lbs) more than 12 Clapham slave owners claimed a total of £6,332 when slavery was finally abolished in Britain.

That is about £603,000 in today’s money and does not include the compensation claimed by George Hibbert, one of the most prominent slave traders who lived and worked in Clapham.

His claim amounted to £53,799 in the 1830s which would be £5,123,000 today. It was based on his ownership of more than 10 estates in Jamaica and 3,549 slaves. This made him and his family one of the richest slave owners in Britain.

George Hibbert was a politician and slave merchant who lived on the north side of Clapham Common in a house called the Hollies which has now been demolished and replaced by the Trinity Hospice. Hibbert came from a family of merchants.

His uncle Thomas was a planter and merchant in Jamaica. He was also a trustee of the chapel at St Paul’s, Clapham.

George was a prominent figure in the building of the West India Docks and was also chairman of the West Indies Merchants organisation. He spent most of his political career lobbying against the abolition of slavery and was the advisor of Henry Thornton, another Clapham resident, on the Slavery Bill.

George Hibbert used his wealth as a merchant to aid charitable causes. He helped in the running and creation of the National Institution for the Preservation of Life from Shipwreck. One could argue that the charity was created to save the lives of slave ship owners and their employees if anything was to happen to them at sea.

This charity still exists today and is now the Royal National Lifeboat Institution, a favourite target of the right wing media for its role in rescuing refugees from the English Channel.

George Hibbert also donated money to “poor houses” which, at the time, were managed by the local parish churches, and the City of London Lying-in Hospital, a maternity unit for poor people.

Known as George Hibbert of Clapham, esquire, he was a prominent figure in the town and well respected.

His brother William Hibbert, Esq was also a merchant who moved to Clapham in 1810 and whose home stood at the start of Crescent Grove in Clapham Common.

Like his brother, William made his fortune from the slave trade. He owned six plantations in Jamaica. It is not known how much George Hibbert claimed in compensation after the abolition of slavery.

His daughters Sarah and Mary Anne built the Hibbert almshouses in Wandsworth Road, SW8, after his death to commemorate their father. They are now run by the Hibbert Almshouse Charity.

John Brett and Richard Cranely were both known for starting slavery in the UK as they traded tobacco and other goods imported from plantations with their neighbours.

We do not know if their neighbours were business owners and sold these goods within the Clapham community with residents. They have not been identified in the UCL database as plantation owners.

It is speculated in many journals that both men had links with plantations in Barbados. It is believed that may have owned the slave ship Henrietta Marie. It was wrecked off the coast of Florida in 1700, and was rediscovered in 1972. It has since become a symbol of slavery.

Clapham was the home of decision-making and distribution of slave-laboured goods across London.

Clapham merchants had a major influence on British politics. Many of them were MPs or were related to MPs through family or marriage.

Directly benefiting from the slave trade, they used their power to make sure that abolition was fought off.

George Hibbert made many speeches in parliament in favour of the slave trade. In February 1807 he made three stating what he saw as the benefits of the slave trade for Britain.

In the early 1790s he had campaigned for compensation for slave owners, claiming that their livelihoods were dependent on the profits they made from slavery

He was also MP for Seaford, Sussex, between 1806 and 1812.

His political power spanned across the Atlantic to Jamaica, where he became an agent between 1812-1822.

He was not the only Clapham merchant to have political connections. John Gould was an absentee slave owner and Clapham resident who was also MP for Shoreham in Sussex.

The power that these men had, not only in their local area but also in parliament and nationally, allowed them to maintain their wealth through the slave trade for a very long time.

British financial institutions also profited from the slave trade and supported Clapham merchants such as Hibbert in the fight to maintain it.

They imported foreign goods that grew the British market and changed the lives of British people, introducing them to new goods and products including cane sugar and tobacco.

When it comes to the building and construction of Britain as we know it today, the Clapham merchants and their plantations helped fuel the British industrial revolution.

One new industry to emerge was the production of cotton cloth using raw cotton, cultivated by slaves.

Slavery provided the raw materials for industrial growth and many factories in Britain produced the goods slave owners needed for their plantations, such as pots and guns.

The national distribution of goods needed railways and George Hibbert contributed to their construction in Liverpool and Manchester.

It is a struggle to trace today the money that slave merchants invested in such projects and received from them in profits to the local towns and parishes where they lived.

How much the Clapham slave merchants contributed to the building of Clapham is unknown today.

Records once stored by local parishes have been moved into the London metropolitan or local council archives.

Pictures of how Clapham looked in those times have also been lost or spread around archives across London, making it difficult to paint a picture of what life would have looked like for the merchants and their families during those times.

Many of the companies owned by the merchants no longer exist as they were mainly created to manage the high demands of the slave trade and collectively create generational wealth with each other and build the infrastructure needed to import and export goods needed to run plantations.

Thank you for telling an interesting if challenging story. It is striking to see how slavery and the proceeds of it were embedded into the British economy. I sometimes wonder if this national involvement can be hidden by focusing on individuals. Would people like myself whose family don’t seem to have had any direct connection to slavery think that it was nothing to do with them? Will they feel that changing a few road names is all that needs to be done? Incidentally, the Zanzibar photograph is a reminder the slavery was a global phenomenon since the slave trade there was controlled by Omani Arabs trading north along and across the Indian ocean.