Pride’s star-studded cast and strong underdog theme should make the film a global hit. The unlikely coming together of London’s gay community with a group of Welsh miners promises to evoke all the emotions. For Brixtonites though, there’s added local interest…

Jonathan, one of the film’s key characters, is a long-standing Brixton resident. And he is being played by The Wire star, Dominic West. So I’m in (the real) Jonathan’s kitchenette and we’re watching the film trailer together. It cuts to a scene on the dance floor of a community hall, somewhere in Wales’ Dulais Valley.

Just one man is dancing amongst the local ladies.

“This is a first, this,” says one of these ladies, to Jonathan, who’s dancing by her side. “Welsh men don’t dance.” Her voice is raised to stand out above the music.

Another lady shouts out in agreement, “Welsh men can’t move their hips.”

Spurred on by this, West’s character jumps into life, throwing himself around the dancefloor to the tune of Shame Shame Shame – his arms and legs are tentacles reaching for the attention of onlookers.

When the trailer finishes, I ask Jonathan “Did you actually dance like that?”

“Oh No,” he says, laughing. “I don’t even remember dancing, but I guess this picture is the proof.”

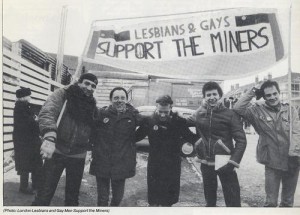

He shows me a black and white image. It’s the Lesbians and Gay Men Support the Miners group (LGSM), in that same community centre in the Dulais Valley. Jonathan stands prominently in the foreground, wearing some distinctive chequered trousers, and evidently cutting some sort of groove.

“They based that whole scene on this picture,” he says. “In fact, the writer, Stephen Beresford, created aspects of Jonathan’s character himself. But a lot of it was real. Look, I made those myself…” He points to the trousers in the picture. “They captured my clothes really well in the film.”

In 1985, Jonathan did a trouser-making course at the Strand Centre on Tulse Hill. It was the time of the GLC, when people could do any number of courses for a pound.

”Livingstone was the bees knees,” Jonathan ruminates. After the course, he went on to study at the London College of Fashion – passing with the highest marks.

“What did I do then… well, I didn’t really fancy Saville Row,” he laughs. “I wanted to find a better fit’. And then his break came. Sat with his portfolio in hand, waiting for an interview in the offices of the English National Opera, Jonathan noticed something on the wall: it was a heartfelt memorial to a staff member who had recently passed away because of HIV.

“That sort of openness was rare back then. And I knew straight away it was a place I wanted to work,” says Jonathan. It was here that he became a ‘cutter’ on numerous shows, and in the film you’ll catch glimpses of Jonathan’s style: the bandanas, the beret (and of course, those chequered trousers).

He stayed with the English National Opera until the mid 1990s – that was when his own health gave out. “Back in 1982, I was an L1 – meaning I was one of the first people in London to be positively diagnosed with HIV. Of course, back then, nobody really knew much about it. You were learning along with the doctors. What saved me though, was that I didn’t get involved in the cohort taking the AZT drug. I didn’t like the research methods.”

Sadly, Jonathan saw most people that took that drug die around him. He became a poster boy for the Terence Higgins Trust. “I remember walking into Clapham North tube one day, and being bombarded by my image on both sides of the platform. I had to walk out, it was a bit overwhelming.”

So, with his health deteriorating further, he eventually had the fortune to meet an amazing doctor, Chris Taylor, at King’s College. Taylor told him he had to do something or he wouldn’t survive long, and they worked at finding the right mix of treatment.

Today, Jonathan shares a home with his partner, Nigel. The two of them have lived in Brixton, as part of a housing co-op, pretty much since they met back in the eighties. Jonathan’s health is under control. But when Jonathan first found out that he had contracted the virus, he admitted that he was not all that concerned about living.

“I tried to commit suicide. But I couldn’t bear the idea of somebody else having to clean it up. Naturally, carrying this killer disease, I had a low self-esteem… certainly, the Sun newspaper was doing its bit to demonise HIV.”

Jonathan’s fortune changed in 1984. He was invited along to a stand against nuclear weapons, down at Aldermarston.

“I remember being very nervous,” he says, “as we took the bus from the ‘Gays The Word’ Bookshop in Bloomsbury. But it was on this trip that I met Nigel.” He smiles. “Nigel was the one that brought me in, got me involved with the LGSM – he was the politically active one – a real socialist – and from this point on I was kept very busy.”

It was around then that some of London’s gay community wanted to support the miners. And that’s the period the film focuses on.

“We saw them, like us, as a persecuted minority. Initially, we wanted to raise money for the National Union of Miners. Their response was that they ‘didn’t want anything to do with poofs,” says Jonathan. “But the Welsh Miners were open to our support.”

The rest, we shall leave to the film. The question is then, does Dominic West do Jonathan justice?

“Well, Dominic came for tea,” Jonathan says. “He sat right there,” pointing to the sofa in the other room. “I made him a lemon drizzle cake… what a charming, unassuming man. What he does with my character is amazing. As I said, there is a lot of creation in the film but Dominic’s notion of Jonathan is very attractive… I’d love to be him.”

“The film won the gay Palme D’Or,” Jonathan continues. “I didn’t even know there was a gay Palm D’Or before that. But the first time I saw it… well, I was overwhelmed with sadness. I mean, I was seeing all these people again – friends that are no longer here because of HIV… The second time though, I really enjoyed it for what it is. The writers, the cast, they’ve done serious justice to the story.”

What’s interesting is the impact that the events of that period have had. “Dai Donovan, one of the fundraisers, was hugely influential in getting gay rights onto the labour parties’ political agenda. Now look… we even have civil partnerships,” Jonathan concludes.

Pride is released at the Ritzy on 12th September.