Steve Powdrill recalls the life and work of Havelock Ellis a radical Brixton resident of more than 100 years ago

Steve Powdrill recalls the life and work of Havelock Ellis a radical Brixton resident of more than 100 years ago

Why do we love who we love? Scientists recently added to the complexity of the question by debunking the myth of a single “gay gene”. For decades, it was believed by many to be what could be the marker-point on what makes up a person’s sexuality.

The high-profile study of over half-a-million UK and US citizens – the largest of its kind to date – now suggests that a mixture of different genes and environmental factors determine sexual orientation.

A study on homosexuality of this scale might seem fairly normal now – but not too long ago, being gay could land you in prison and LGBTQ+ research was biased, limited and meagrely funded.

A previous Brixton resident would know all about this – and be the very first to try and make it right.

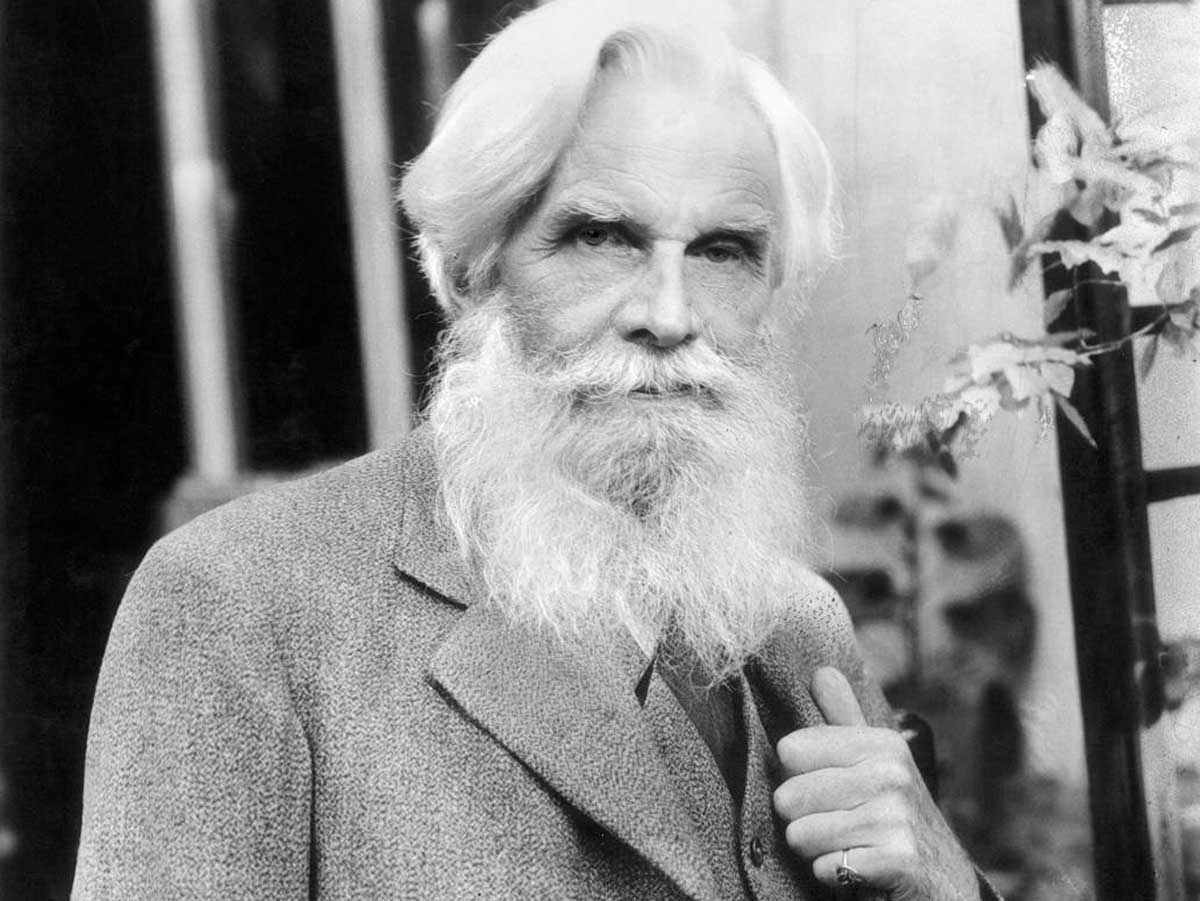

There’s a blue plaque high up on Brixton’s Canterbury Crescent, honouring Havelock Ellis (1859 – 1939), who lived in the area at around the same time as Vincent Van Gogh in the late 1800s.

He was a progressive physician who dedicated his life to human sexuality, writing the first book to explore homosexuality as a natural occurrence rather than an immorality or perversion.

In a buttoned-up and sexually awkward Victorian society, his book was highly controversial and withdrawn from some bookshops, vehemently labelled, “lewd, wicked, bawdy and scandalous”.

But Ellis was not the type of man to step back from his convictions easily. Born the same year that Charles Darwin published revolutionary ideas on evolution, but raised mainly by an “ardent Evangelical Christian” mother, Ellis learnt early to form an individual point of view. He saw religion to be “dying”, in a Victorian era where scripture influenced strict and iron-fisted social expectations.

Science, on the other hand, provided him with an alternative route – a humanist standpoint, where people’s natural desires were not repressed but freely explored, for this, he believed, could produce a happier society.

Armed with a passion for sexology and a loan from his mother, young Ellis studied to become a doctor at St Thomas’ Hospital in London for eight long years. While not particularly successful in the medical field thereafter, he made headway writing texts on little-discussed topics such as masturbation and making contacts with other liberal thinkers of the time, such as Eleanor Marx, Edward Carpenter and Edith Mary Oldham Lees – the latter would become his wife.

Their relationship would be far from conventional, with Edith being lesbian and maintaining multiple female lovers throughout their marriage, of whom Ellis was aware. While the pair eventually separated, Ellis wrote fondly of Edith thereafter, admiring her intellect and academic writing.

Ellis himself was sexually ambiguous, seemingly preferring platonic relationships with women, though he often wrote about his fetish for “urolagina” – female urination.

As was the case with much of his work, critics were outraged at his transparency in discussion of sexual taboos – but his honesty and earnestness in helping society to see past them earned Ellis a considerable fan-base. After publishing Studies in the Psychology of Sex, the series that argued for open discussion of sex and homosexuality over fear and ignorance, thousands of readers wrote to him for advice on their own sexual issues.

In this way, Havelock Ellis was something of a champion for sexual freedom, educating repressed Victorians and helping to chip away at hardened taboos. He was also a friend to LGBTQ+ people, admitting to writing so committedly about homosexuality because of his close friends (including Edith Ellis and Edward Carpenter) being gay.

In fact, they featured in his book themselves as case studies, with their names changed, as well as helping to provide Ellis with more gay subjects to interview in his research.

Despite these years of research, Ellis knew better than anyone of the broad complexity of human sexuality – perhaps he knew we would still be debating it now.

He wrote in 1927: “As a youth, I hoped to solve problems for those who came after; now I am quietly content if I do little more than state them … if I cannot perhaps turn the lock myself, I bring the key which can alone in the end rightly open the door: the key of sincerity.”

Havelock Ellis died in 1939 at his home in Ipswich with his partner at the time, Francois Lafitte-Cyon and her two sons.

He had written his autobiography, My Life, with the intention that the sales would be used to provide for the family, but Britain was on the cusp of war and sales were scuppered as a result.

Nevertheless, his legacy lives on, with much of his work building momentum for the decriminalisation of homosexuality in 1967 and the gay rights movement that would follow.

Next time you walk along Canterbury Crescent, from the police station to Pop Brixton, spare a glance and a thought for the man who dedicated his life to educating the masses and fighting for the oppressed – because, as he said “when love is suppressed, hate takes its place”.