The Foresters of Trinidad meet the Foresters of Seaford

Brixton’s African Caribbean war memorial in Windrush Square gives long overdue recognition to servicemen and women who fought for Britain. But, as Dolores William, discovers, it is not the only place they are remembered in England …

Audio Player

Two days after the first Remembrance Day service at the war memorial in Brixton dedicated to West Indians and Africans who fought and who died for Britain in the great wars, I’m at another ceremony.

It’s freezing cold and I’m standing in the Commonwealth war cemetery in the seaside town of Seaford in East Sussex, surrounded by the beautiful South Downs.

War veterans in uniform representing the regiments of the fallen have gathered – Ireland, Canada and the West Indies.

The High Sheriff of East Sussex, Maureen Chowen, and Commander Corey Bursey, assistant naval advisor at the Canadian Embassy, are among those gathered, as are a small contingent of West Indian ladies and gents who have come from London to pay their respects.

As I watched a lady gently walking among the graves, curiosity overcame me. I introduced myself and it turns out the lady is a relative of two soldiers who are buried here.

Great uncles Nelson and Dennis Fevrier – their descendants grew up hearing about the brothers who went away and never came back.

Later I would sit down and talk to the cousins, Timothea, who I had met by the graveside, Judith Fevrier and Esther Marcelle.

They found their relatives after a call out by the Clapham-based West Indian Ex-Servicemen’s Association to find relatives of some of the West Indian servicemen buried in Seaford.

They realised a new respect for Remembrance Day services, admitting that, before, they didn’t feel that they meant anything to them as they had no knowledge that they also had family buried in war graves in a tiny English town for nearly 100 years.

The discovery made big news on the island of St Lucia where a ceremony was held for the brothers.

They never fought in the war, but died of pneumonia in Seaford. The change in climate from the sunny West Indies to wintery Seaford, combined with being confined to poor accommodation with inadequate clothing, was too much. Unable to do much training or get any exercise, several developed pneumonia, and then an epidemic of mumps swept through their ranks.

Between October 1915 and January 1916, 19 West Indians died of mumps or pneumonia.

So sad to think they came so far to fight for the British empire. West Indians were stowing away to get to England to fight. In May 1915 nine men from Barbados appeared at a court in East London after being found on a ship in nearby docks.

They were taken to the nearest recruitment office where they were duly rejected for being Black. This caused such a rumpus that King George V got involved and set up the West Indian Contingents.

The cousins told me that they thought the Black soldiers had been treated unkindly by the town’s folk and the military. It’s true that Black soldiers were paid less.

I spoke to local historian Kevin Gordon, who gave me some insight into how the soldiers were treated. He says that, as in a lot of towns along the Kent and Sussex coast, Seaford people thought they would be inundated with refugees and foreign soldiers. There was apprehension about the West Indians.

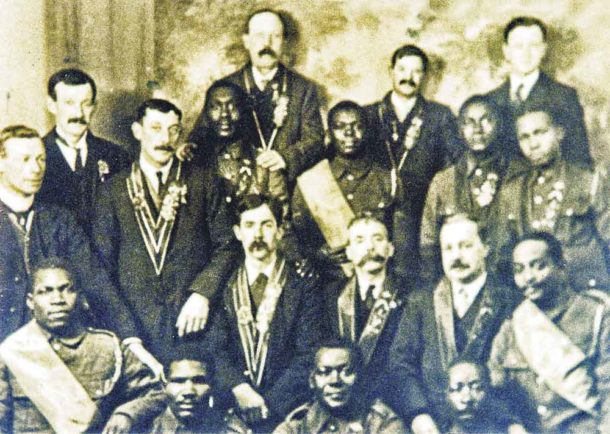

But it was not long before the boys from the Caribbean, all 750 of them, marched into town up to the North Camp and were being called “The Westies”. The behaviour and smart uniforms of the boys when they were off duty endeared them to the locals. Kevin told me an amazing story: the Seaford branch of the Ancient Order of Foresters, which had many members serving in the armed forces, discovered that several of the West Indian soldiers at the North Camp were members of their own organisation.

They were invited to attend local meetings. During one, Private Clement of the Pride of Hope Court of the Foresters of Trinidad said: “We have left our homes and comforts because the call-to-arms is as much to us as it is to an Englishman. We are all British and are proud to be members of the Empire and we will shed our last drop of blood to uphold its integrity.”

There is no doubt that there was discrimination, but I think the relatives can find a little comfort that these brave guys were treated with much respect by the people of Seaford.

In November 1915, a group of Black soldiers marched in the Lord Mayor’s Parade in London. The Daily News called them “huge and mighty men of valour”.