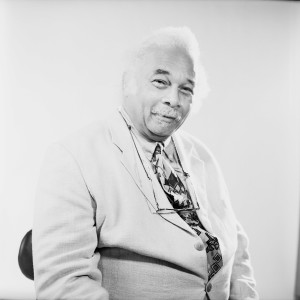

Charlie Phillips has been capturing black London on camera for fifty years and this month, he presents a unique collection of his work at Brixton’s Photofusion focussing on Afro Caribbean funerals. Arts co-editor Ruth Waters finds out more about the man behind the camera.

As a boy, Charlie Phillips didn’t dream of becoming a photographer: “I should have been an opera singer or a naval architect, those are two of my passions, or perhaps I should have been a priest, that’s what my Grandmother wanted” Charlie muses. “I came to have a camera completely by accident.”

Charlie came to be the proud owner of a camera when a worse for wear American GI pawned a simple camera to his father to earn his fare back to the base. His father gave him the camera and so began his journey documenting the life of his neighbourhood, then Notting Hill. “I didn’t think anything of it, I was just taking pictures of people in my community and developing them in our communal bathroom. Even recently, I didn’t realise I had such a collection.”

Charlie made his name as a photographer in Italy, having travelled with the Merchant Navy, he developed the craft of documenting counter culture and social uprisings, photographing student protests in Paris and Rome, as well as working as a paparazzo photographer, capturing the likes of Pavarotti on film. “There was never the platform for my work in this country. The art world was and was too elitist” he tells me.

Charlie’s iconic images of the people of Notting Hill in the 60s and 70s have more recently gained at least something towards the status they deserve and Charlie was part of a three man exhibition at the Museum of London eight years ago. “The funny thing is, when I exhibited my work alongside two other photographers of colour at the Museum of London in 2006, people were saying to me, ‘How come we haven’t seen your work before?’” What kept Charlie interested in documenting London over the decades, despite the constant barriers that the art world put in front of him? “Growing up in London, I always had a curious mind, and I guess that never went away.”

As an experienced documenter of large-scale social movements, I wonder why Charlie’s upcoming exhibition focuses solely on Afro Caribbean funerals. “The first funeral I photographed was my Aunt Susie’s in 1962. Our community in North West London was close and whenever someone died we would all go along, and I would take pictures. I only realised I had such a big collection when Lizzy [King, Co Curator and Community Programme Manager at Photofusion] came over and rummaged in my loft.

“What I realised was that my photos taken in the 60s, 70s, 80s showed the changes in fashion for Afro Caribbean funerals. The fashion, the style, the procession, it’s all changed”. The dress changes from the traditional colours of black, grey or purple, to being bright colours only; the music choices from hymn “How Great Thou Art” to “I did It My Way” by Frank Sinatra or “Simply the Best… The question I began asking myself was, are we losing part of our culture, should we stick to tradition?”.

I ask Charlie about what he think is important to include in a funeral, his answer strives for a balance between the celebration of the individual and a celebration of the traditional. “I have written my will!” he says triumphantly, “and I know what the music will be: it will be “How Great Thou Art” followed by the Slave Song from [the opera] Nabucco, because I’m an opera fanatic”.

I am curious to find out what Charlie views as special about Afro Caribbean funerals. It’s clear that, starting from when he was a young man, Charlie sought to document the world he knew, and still has a firey passion for “grassroots art” and representing the working class in the art world. But, as well as this, there’s a sense of joy and celebration which his photos capture: “Afro Caribbean Funerals are not about dying only, it’s a celebration of that’s person life.”

Aged seventy, Charlie’s stamina for exhibiting and sharing his work is remarkable. “I should be resting in my retirement,” he half jokes, “I just wanted time to read War and Peace, tend to my tomatoes and grow some roses.” But the thing which spurs him back to work is a dedication to preserving an era of London, recording his community from the inside. “Kids come up to me now, the fifth generation [of British Afro Caribbeans] and want to know if I have a photo of their Grandfather, their Great Grandfather…they want to know more about their past, and what should I tell them? To go away? I don’t think so.”

How Great Thou Art opens on 7 November and runs until 5 December. Entry is free and everyone is welcome.