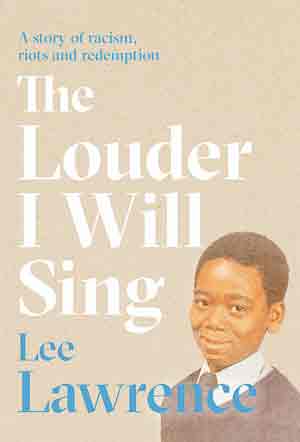

Lee Lawrence talks to Dave Randall about his prize-winning book that recounts the police shooting of his mother Cherry Groce in Brixton and its aftermath

Dave Randall: Lee Lawrence, thank you so much for agreeing to do this interview with the Brixton Blog and thank you for writing what I think many people will agree is a very important book, The Louder I Will Sing.

The book is about a number of different things, isn’t it? But it is in large part the story of your attempt to understand and then seek justice for an incident that many people here in Brixton will remember – one that took place back in 1985 when you were just 11 years old. Do you want to take us back to that time? What was Brixton like at the time? And then what happened that fateful morning in September?

Lee Lawrence: It’s very important for me to be able to depict Brixton in the way that I saw it, because Brixton over many years, and especially back then, was kind of portrayed as this dangerous place that you wouldn’t want to be caught late at night in and this kind of real hostile environment – which wasn’t my reality as a child growing up in Brixton.

It was fun, it was exciting, it was safe. We never locked our doors. My door was wide open, so I wouldn’t even need to a key. I walked in through the back door all the time.

We played out in the streets, we were in and out of each other’s houses. It had a real sense of community spirit. That’s how I felt. I always used the phrase: ‘It takes a village to raise a child’.

That’s the type of place I felt that I lived in. My mum’s friends were like my uncles and aunties. That’s how I would view them.

And then there was also a sense that the community policed the community. So therefore, when there were any issues within the community, we sorted them out ourselves to some degree. And you always knew somebody that knew somebody that could sort something out.

That’s how it was for me growing up in Brixton. I also grew up around the time of the Rastafarian movement. So there was a lot of that kind of conscious vibe going on as well. So referring to each other as brother and sister and, you know, that kind of that kind of love, you know, that, you know, if you think about Bob Marley’s music, you know a lot of that kind of vibes in a very positive place, very positive.

I’m a kid and this is how I’m seeing it through my eyes at that time, you know, and I love living in Brixton.

So that was Brixton pre the incident.

You know, we were poor. And so therefore, that had an effect. We knew we were poor. We didn’t have much. I saw my mum struggle. So that struggle was real every day, struggling to put food on the table. And you knew that, as Black people, we were dealt with disproportionately – meaning that you saw we were treated differently and were conscious at a very young age.

I was taught that ‘if you see a gang of white boys, run’. That’s what we were told. So you were aware of racism and you were aware that you could be attacked because of the colour of your skin. But I wasn’t aware of necessarily the police – the issue with the police and the community at that time, I was not aware of that as a kid before the incident.

DR: Do you remember the 1981 uprising, would you have been old enough or not quite?

LL: Not quite old enough, I mean, that would have been when we just moved to Brixton, so I haven’t got much memory of 81 and how it impacted on the community.

DR: So there you are – a happy childhood in a positive place to be growing up, enjoying your BMX, enjoying the music that your mum likes to play at home, enjoying your friends and neighbours and family.

And then what happens in September of that year, 1985, if I can take you back to this tragic incident that really forms the core of the book?

LL: This was something that would change my life forever. It was the first time that I had witnessed any sort of violent crime in that respect and the trauma of that that still lives on.

It was the 28th of September 1985. It was Saturday morning, 7 am. And we were asleep in my mum’s room. And I heard a noise.

I saw my mum get up and walk towards the door. I thought, whatever it was, mum’s taking care of it. And fallen back off to sleep.

And then, the next thing I knew, I heard another loud bang! Jumped up. This time and fully alert. And my mum is lying on the floor and the man – got a gun in his hand – is just shouting at my mum, saying ‘Where’s Michael Groce? Michael Groce?’ in this aggressive way.

I just hear my mum in a very faint voice say ‘I can’t breathe, I can’t control my legs and I think I’m going to die’.

That freaked me out. I saw my mum lying there vulnerable and I was just screaming and shouting at this man who had the gun in his hand.

I thought, what has he done to my mum? What are you doing to my mum? I was effing and blinding and everything. I just felt like I want to attack him to be honest.

And then he turned round, pointing his gun towards me, and said ‘someone better shut this fucking kid up’ like … or else. And as if I was annoying him.

In that moment, there was no sense of compassion for what happened, there was no sense of, ‘Oh, my God, I’ve made a mistake’. It goes nothing like that. It was just almost like you’re just annoyed that you haven’t got the person that you wanted to get.

DR: So initially you weren’t clear who this intruder was. He’s asking after your older brother who doesn’t even live with you at the time. You don’t know who he is.

LL: Exactly. At this point, I didn’t even realise this was a police officer. It was only when my dad said: ‘Lee, calm down’ and I saw the fear on my dad’s face that I realised, Oh, my God, this is serious. My dad used to be in the army and he was a security guard at the time. So I thought: ‘my dad’s scared, this is serious’.

And then we got ushered out of the room. And that’s where I saw like about 30 police officers in the house … dogs and guns.

It was madness. It felt like our house has been invaded, and I thought I was still dreaming, to be honest.

Ans I was confused because I thought these are supposed to be the good guys.

You know, I grew up wanting to be a police officer, so I’m watching all the programmes on TV. I’m thinking how can these guys come in and shoot my mum, my innocent mum, in front of us, and be so aggressive towards us, like we’ve got like we’ve done something to them.

After that, my mum was in the bedroom for a little while. I tried to get back into the room and I got past the police officer. And I said: ‘What’s happened to my mum’, because in some senses, I realised that she must have been shot. But I’m still confused about did she get shot? Did she got shot? What happened? So I said, what happened to it? And they said: ‘Oh, she just got grazed’.

I said: ‘if she’s got a graze, how come she’s bleeding so much?’ And I could see the blood pouring. And then he quickly rushed me out the room at that point.

An ambulance came after a while. My mum went into the ambulance and we were left in the house. I was 11. My sister Lisa was eight, my sister Sharon, 13, my sister Juliet, 24 and six months pregnant. And there were two other children in the house that my mum was babysitting, a two-year-old and a seven-year-old.

So now we were left on our own, but my mum’s gone to the hospital, my dad’s gone, and they allowed the press to come in and take pictures of us. They lined us up on the sofa – all crying – and took pictures of us. It was just mayhem. It was a combination of shock, trauma, fear, anger, confusion.

All these different emotions were coming all at the same time or at different periods of time.

And the next thing … I just know that crowds were building up outside the house, demanding to know what had happened.

We were getting updates on the news, and they reported that my mum had died. So I tried to commit suicide at the time and one of the female police officers took the knife and away from me.

DR: Thankfully, the reports were wrong. Your mother was alive. She had been paralysed, though, by the shooting. But word spread that she might have been fatally injured. And a crowd started to gather, of course, outside Brixton police station.

LL: That’s correct. And they weren’t getting any answers.

It’s a classic kind of situation and tensions built up, and frustration and anger. On top of it, the police officers were saying racist words to the crowd as well, so inciting violence as well.

And before you know it, it had kicked off. It is now famously known as the Brixton riots of 85. I call it an uprising. The reason why those people went to the police station in the first place is because an innocent mother was shot in front of her children.

DR: And that was very significant for the family. That felt like an important act of solidarity from the community. That meant a lot to you.

LL: It meant a hell of a lot, it was comforting. Now, of course, I don’t condone the violence and the looting, but I know why those people came together in the first place – because it was almost like only we understood within that community what happened and what happens.

Outside of that, people might be: ‘Hmm, really? Could the police really go into a house and shoot an innocent woman?’

But for us, we know where we are. Four years before that we had the 81 uprising. Now it’s like, OK, it’s getting worse. They’re coming into our homes and shooting our women in front of our children. But where do you draw the line?

DR: One of the many brilliant things about the book for me is the fact that you do explain the context in which a tragedy like that could take place.

You talk in detail about incidents of institutional racism and police brutality going right back.

You quote the Enoch Powell speech famously called the “rivers of blood” speech. And Thatcher using the word “swamped” in a speech about immigration.

You talk about the Scarman Report following the 81 uprising. And so it reads as a brilliant social history. I mean, I would recommend this book on so many levels. But back to your story in the immediate aftermath of this terrible incident. For a long time, you became, I think, perhaps and one of your sisters, became the primary carers for your mum. Is that right?

LL: That’s right. I remember going to the hospital a few days after the incident and the doctor announcing that my mum was paralysed from the chest down, essentially, and she would never walk again.

And those words were devastating … to see her face when that was explained. And then that moment I made a commitment in my head that I was going to care for my mum.

So I said to myself: ‘I can’t rely on my mum in the way that I did before. Now I’ve got to be there for her’. So myself and my younger sister, Lisa, we became the main caregivers for my mum for the 26 years that she survived confined to a wheelchair.

That was tough, because it robbed us of our childhood. My schooling was interrupted, my social life was interrupted and we didn’t get any therapy. There was no kind of ‘aftercare’. It was just: ‘You just got to get on with it and find a way to survive through this madness.

DR: And it was really only after your mum died in 2011 that you had the opportunity to seek some sort of justice or seek the opportunity to set the record straight, because there was a coroner’s report which said that she had died as a result of the injuries sustained back in 1985 when she was shot by that inspector from the Metropolitan police. And that allowed you to demand an inquest. Tell me about the findings of that inquest, which you finally managed to bring about.

LL: There were multiple serious failings. Eight different accounts, to be precise, It was concluded that the police should have never been in my home that day.

Now, the internal [police] investigation report that was done immediately after it was concluded in 1986.

That senior officer, who was well respected, really concluded that this should never have happened and there were loads of mistakes made.

DR: That wasn’t available to you or anyone else outside of the Met at the time, right?

LL: That’s correct. And that never formed part of the criminal trial and none of that was unveiled.

The officer who shot my mum had been drinking the night before he went on the raid and he was the raid leader. You’ve gone and put him in charge and put a gun in somebody’s hand who’s been out the night before drinking. When you look at how they spoke about us, when you look at what they were planning – to think that we’re in our home sleeping as a family and you’ve got a group of people in Brixton police station planning to mount this raid as if they’re going in for a bunch of terrorists, right?

So to hear, to read that, it was almost like ‘now I can see why my mum got shot’. Someone was going to get shot, that day.

DR: For people who haven’t yet read your book, I think it’s important to say that you share a number of other shocking examples of institutional racism that you’ve witnessed or experienced. And it’s a very powerful testimony. You must be immensely proud to have got this book written to get the story out there. And indeed, now you are the winner of a Costa Prize, a prestigious book prize, in the nonfiction category. You must feel immensely proud of your achievements.

LL: Yeah, there was a sense of pride.

One, because how much this book means to me. First of all, it’s a dedication to my mum and to honour her legacy. And it’s to recognise what we went through as a family and the impact of that.

And, also, I’m aware that our story is one of many. There are so many people who haven’t been fortunate enough to have had their voice heard. So it’s to be able to show an example of one of many stories from a personal perspective, because for years we were just reported on.

My mum was just known as this woman who was shot by the police.

So now we’ve got to tell our story. We’ve got to get the truth out there in terms of what really happened. It’s something that I know that my mum would be immensely proud of as well. So it means a lot to have that that recognition. And it also allows the book to maybe reach audiences that maybe we wouldn’t have before, being acknowledged in this way.

DR: There is a very, very beautiful epilogue in the book where you talk much more about your mum, about Cherry Groce than you. And really, you underline the fact that she, of course, was so much more than the victim of police brutality that dreadful day in 1985.

You sum up that epilogue by saying that you remember her as somebody who was dancing, always dancing, which I find profoundly moving when we’re talking about somebody who, of course, was paralysed from such an early age.

Just after the epilogue, you mention, briefly, the Black Lives Matter movement, which, of course, began back in 2015. But it really exploded last year following the murder of George Floyd in America.

I wanted to share with you the fact that I attended one of the first Black Lives Matter protests that took place in Britain after the murder of George Floyd. It was in Brixton. It was organised and led by young women of colour, probably in their 20s, and it weaved around the back streets of Brixton. And then the leaders of the march called a stop outside 22 Normandy Road. And on the megaphone, they explained the significance of this address and the significance of the story of your mum, Cherry Groce. Does it give you hope to see this new generation of anti-racist activists emerge?

LL: It does, it does. I went on one of the marches myself when I bought my daughters with me who are aged 12 and eight. I thought it was important for them to witness this because, number one, it’s part of where we’re coming from.

I feel so indebted to the community for rising up in the way that they did in support of what happened to my mum. And they probably would never be recognized in the same way if they didn’t.

So any time I get an opportunity to lend my support then it’s something that I try to do. And when I went there and I saw so many people this time around who didn’t necessarily look like us, but are now empathising with the situation and are behind the cause of want to see a more fair and just world – that gives me hope.

And there were people that had placards with my mum’s name on it. That was nice to see that she’s remembered – she’s still a part of this ongoing legacy of change.

If we’re able to use what we’ve gone through in terms of that terrible experience to help shape the future somewhat, it’s never going to be well in terms of what we went through, but at least it won’t be in vain. At least we’ll be able to use that to hopefully try and turn things around in a positive way.

DR: Writing the book must have been, emotionally speaking, very difficult and indeed doing interviews like this, having to go over these very traumatic events.

How are you finding this process?

LL: There’s a saying I’ve got – that the purpose outweighs the challenge – and that’s a motto that I used going through my process.

It’s challenging to always connect to what we went through. And when I’m doing an interview, I like to be as authentic as possible.

So when you when you talk to me and you say to me, what happened, I’m in the room, but I’m telling you what’s happening. I see my mum, I see the police officer. I know where I was positioned in that room. So that can be emotionally draining.

However, I see the benefit of bringing the story to the forefront in terms of whether it’s people being inspired, whether it’s people being educated and made more aware of the situation.

I’ve had so many people reach out to me.

I recently had a police officer reach out to me and say that when he read the book, he was in tears. He wanted to make contact to see how he could be a part of that change as well.

So to see the book touching so many people in such a positive way, I mean, their lives, to me that is the measure of the success of the book.

It is really hopeful to see that, but, also, I’m a realist. I know we have still got a lot of work to do and we’ve got to keep the momentum up.

We can’t afford to have this sort of big moment for it to go really quiet again until we have another moment.

You know, what are we going to consistently do to to make sure we’ve got consistent change?

DR: I think it’s an absolutely brilliant book. I strongly recommend that everybody reads it and I will be recommending it to everyone I speak to.

I mean, I’ve read a few books – even books have won, awards – that don’t ring true, that seem a bit hammy for me. You know, leave me wondering quite why they got the acclaim.

Your book absolutely feels so heartfelt and honest and actually it’s extremely compelling. It’s a page turner. It’s brilliantly structured. I think it’s a huge achievement. What’s next? I know that you’ve set up the Cherry Groce Foundation. Are you going to do more writing? What’s next for you, Lee?

LL: First of all, in terms of what’s in front of me now, I want to make sure that, for instance, with the book, I want to make sure that I do everything I can to make sure that the book spreads as wide as possible in terms of that message and the mission that I’m on to have this be a part of the change that we need to see going forward. So that’s one thing.

The other thing is that, as a result of what we went through, there was restorative justice and restorative justice outcomes and fulfilling those outcomes.

One is to have the permanent memorial erected in Windrush Square, in my mum’s name, in honour of her and the community. We should hopefully have that erected on 24 April to coincide with the ten years since my mum passed. So that’s something I’m really looking forward to, the memorial designed by the world famous architect Sir David Adjaye. I’m really proud of what he’s put together.

That will also form part of an education programme and training for police officers. What we’re looking at doing is new recruits that come into Lambeth will be educated on the history of this community and why this community is so sensitive when it comes to policing.

DR: Fantastic. Well, it’s been an absolute pleasure speaking with you. Thanks again for sharing your story in this brilliant book.