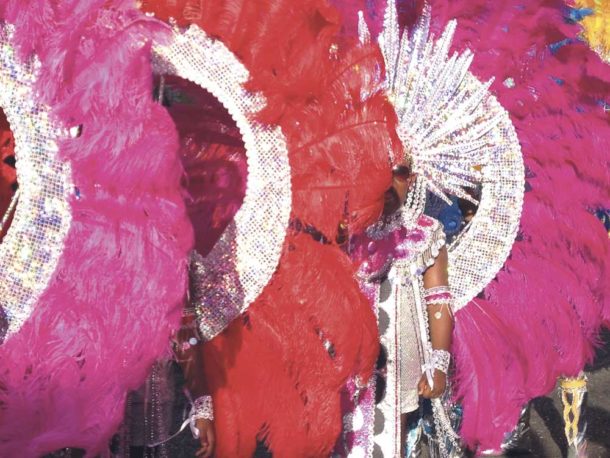

On a visit to Trinidad Dave Randall discovered that there is more to carnival than a good time

Aside from the moving corporate celebration of buttock-shaped hearts and red roses for St Valentine’s Day, February is all about Pancake Day. At least that’s what I thought as I grew up under the grey winter skies of South East Essex.

But on becoming an adult and moving to London, I learned that the same day takes different forms in other latitudes. As kitchens here are crammed with eager tossers, millions of people elsewhere take to the streets for carnival.

A couple of years ago I decided to give my frying pan the night off and travel to the home of one of the world’s largest carnivals – the Caribbean island of Trinidad.

I discovered that carnival’s rich traditions arise directly from a clash between oppressed people determined to reclaim time, space and pleasure in their lives and a ruling class who feared them.

My education began at Port of Spain’s Carnival Village, where I met Barry, from Trinidad and Tobago’s steel pan union. The glint in his eye, I soon learned, was not from any fondness for the British, but from thoughts of a much celebrated riot against them.

The pre-Lent masquerade, he began, arrived on the island with French “planters” forced from Haiti by the revolution of 1791–1804. Slaves were excluded from the festivities.

After the formal end of slavery in the 1830s, former slaves and other workers made their own celebration of Canboulay. Barry speculated that the term came from the French for burnt cane: cannes brulées. People would set fire to the crop that symbolised their oppression and then parade into town in celebration.

Masks were worn partly to disguise identities, thwarting attempts to pick out individuals for retribution. When, in 1846, the authorities banned masks, mud and paint were used instead. To this day, Carnival-goers cover themselves in mud and paint during the J’ouvert (day break) procession.

The musical origins of carnival lie in West African “kaiso”

– narrative songs, long used by slaves to mock oppressors.

The plantocracy hated Canboulay, seeing it as a powerful symbolic challenge to their authority. Restrictions were piled on carnival until, in 1881, the British tried to stop it altogether.

Captain Arthur Baker and his men waded into the crowd with truncheons, but people fought back in the legendary Canboulay riot, forcing the police to retreat. Carnival was saved.

Ruling class opinion was divided about the next move. An investigation for the Colonial Office advised: “I think to stop it altogether would be a measure that would justly be regarded as harsh and might lead to serious dissatisfaction on the part of the working classes”.

In 1883 a new strategy was tried – the rulers would ban not the procession, but its musical heartbeat, the djembe “skin drum”. Musicians responded creatively and set about exploring the percussive qualities of the island’s abundant bamboo. Bamboo groups, or “tamboo bamboo” (from tambour – French for drum) soon became the sound of carnival.

Players tended to come from the rougher parts of town and running street battles between groups were commonplace. But it’s unlikely that public safety was uppermost in the minds of the authorities when, in 1934, they stepped in again – to ban the tamboo bamboo.

Trinidadian calls for self-rule and universal suffrage grew in the first decades of the 20th century. Troops were sent to break a dockers’ strike in 1919 and, with the hardships of the Great Depression spreading to the islands in the 1930s, the ideas of militant nationalists gained ground.

The colonial regime, determined to keep people off the streets, in 1936 introduced Ordinance 23, banning “suggestive” dancing, profane songs or songs “that insult members of the upper class”. The Second World War provided to pretext to stop carnival altogether. Musicians bided their time and explored alternatives to bamboo.

When the US joined the war its navy commandeered large parts of Trinidad, littering it with oil drums. In areas like Laventille in East Port of Spain musicians got to work and noticed that the tone produced at the start of a playing session changed as the drum became dented. They developed a tuning system and something similar to the now familiar tuned steel pan was revealed to amazed revellers at Trinidad’s VE Day celebrations in 1945.

The much loved steel pan – one of the few acoustic instruments to have been invented in the twentieth century – exists only because of the creativity and determination of ordinary people facing political repression. The instrument symbolises our indefatigable desire to express ourselves through music.

Barry went on to describe how, in 1951, an all-star delegation of pan players was sent to represent Trinidad and Tobago at the Festival of Britain, starting a love affair with the instrument here. Radio broadcasts and a three-week tour were hastily arranged. One of the earliest photos (left) of a steel pan orchestra being enjoyed on the streets of London was taken in south London in 1961.

One August bank holiday three years later, during a street party in Notting Hill, the Russell Henderson Steel Band spontaneously led a parade around the surrounding streets. In so doing they inspired the creation of the annual Notting Hill Carnival – now the largest street festival in the northern hemisphere.

How many of the party people know, I wonder, that the event owes its very existence to a more or less unbroken sequence of acts of political defiance and creative ingenuity stretching back to the Haitian revolution of 1791?

So, as you tuck into your pancakes this month, be inspired by the thought of all those who are taking to the streets. Theirs has been a long fight for the right to party.

Dave Randall is a musician and author of Sound System: The Political Power of Music