Max MacBride recounts the eventful history of Brixton’s Ritzy cinema

Many things are synonymous with Brixton. The kaleidoscopic market, the Academy, queuing for the Tube, the street preachers and buskers, roofdogs, Franco’s; the list goes on. And to that list, you’d have to add the Ritzy cinema. A bona fide local institution, it has been entertaining and inspiring Brixtonians for over a century, through good times and bad, riots and regeneration.

Of late though, it’s been making headlines for the wrong reasons, as the recent pay dispute with workers threatened to undermine considerable reserves of goodwill from the local community. We decided to take a look back at the recent history of the cinema, and to speak to a couple of the key players in its development from the late seventies onwards in a bid to better understand the DNA of the place and its role in the community.

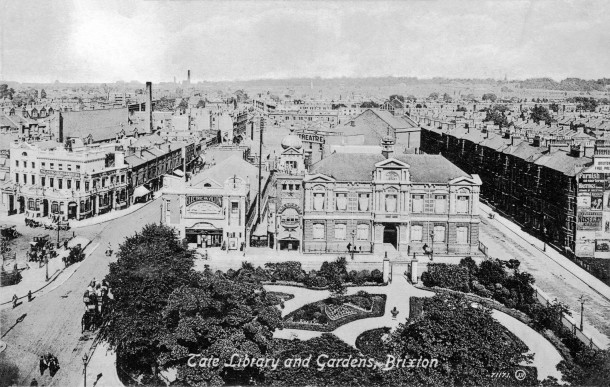

The Ritzy began life as the ‘Electric Pavilion’ in 1911, a welcome addition to Brixton’s booming arts and nightlife scene of the time. The Pavilion was one of England’s earliest purpose-built cinemas, and like many silent cinemas at that time featured an organ by the side of the screen. However, complete with a leaky roof, it was seen as the scruffy relation to the nearby Palladium, and was known as the ‘flea pit’.

Not to be daunted by such mockery, the Electric Pavilion soldiered on for the next 43 years as an important cinema in South London, moving to sound in 1929 and surviving competition, the Blitz and economic hard times along the way. In 1954 a man named George Coles renovated the cinema and renamed it ‘the Pullman’; the organ didn’t survive this change but the grand Edwardian interiors and atmosphere remained intact. It was later renamed ‘the Classic’, and after an inglorious period including a stint as a porn cinema, finally closed its doors permanently in 1976, by that point forlorn and abandoned.

Enter Pat Foster, a young film enthusiast who would go on to reinvent the cinema and lay the foundations of the modern-day Ritzy. I spoke to Pat, still a Brixton resident but no longer involved with the cinema. Pat recalls chancing on an article in the South London Press suggesting that Lambeth Council, which had bought the land in the early seventies, was now looking for ideas of what to do with the space. Although it later transpired that the story was completely made up, it provided the necessary spark for the enterprising young Pat to pitch to the council his vision of the space as a quality independent and arthouse cinema.

Competitors for the space included the Black Theatre Group (an idea which the council also liked, but which would have required a lot of public money) and a carpet warehouse. Although supportive, the council couldn’t provide any funding. Pat, in desperation, placed an ad in Time Out in 1977 appealing for partners to help provide the outstanding £5000 and join his co-operative. Happily, the response was overwhelmingly positive, so with partners and funding secured Pat was able to set about his mission – “with the enthusiasm of the completely ignorant” – to bring great film back to Brixton.

Pat and his team faced a monumental task to put the cinema back in working order though. Having been derelict for two years, the innards had all been sold off; gone were the projectors, seats and power systems. Nevertheless, Pat says some of his fondest memories of running the Ritzy are from those early days, overcoming the myriad obstacles on their relative shoestring budget.

On one occasion, having already acquired some seats for 50p a pop, they heard that a cinema in Hammersmith Broadway was being sold. Seizing the chance to lay their hands on a much needed bit of electrical equipment (which would have been thrown away), they launched a late-night raid. On arrival it turned out that the display board (the bit where the films and marriage proposals are mounted) was still intact too, so they worked through the night to dismantle it – “an absolute nightmare”.

A DIY stage was sourced via spare floorboards and joists in a house being dismantled in the nearby squatted Villa Road. A stern council safety officer would later declare this stage unfit for use, prompting further frantic efforts to get it into shape. The cinema eventually opened its doors in 1978 under the name ‘Little Bit Ritzy’.

In the early days the cinema was very much focussed on showing independent and arthouse film. Pat describes the atmosphere as unashamedly “artsy” – a cinema for film purists, even though he admits their efforts to keep the auditorium as a “sacred place” free of chatter had mixed results. Standard-issue popcorn was eschewed in favour of carrot cake, and although they did eventually relent on that front, Pat is proud that a hot dog never darkened his doors. Late nights were a different story; they took a relaxed attitude towards punters seeking a “a smoke and a flop-out” at the regular after hours double-bills.

The building at that time was very different – beautiful but run down. Although it was listed, the elaborate Victorian facade had been largely stripped out, and the area where the box office is now was not owned by the cinema at that time. “People used to come into the drab foyer,” says Pat, “then when they came into the auditorium, there was often a visible intake of breath. It’s still my favourite auditorium – it’s just beautiful.”

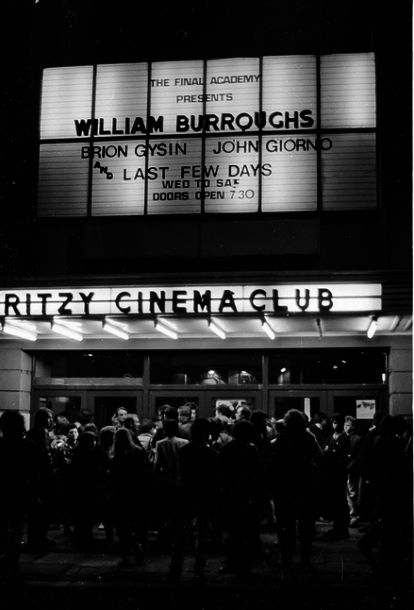

Prohibitive fees and the single screen (distributors would often demand a minimum screen time commitment per week) made access to high-profile Hollywood films difficult early on, although Pat says it was always the aim to begin to work these into the programme. Indeed, a three week showing of Superwoman in 1984 would eventually pave the way for more mainstream programming and greater financial stability. Nevertheless, in the early eighties Little Bit Ritzy (or simply ‘the Ritzy’ as it soon became known) established itself as home to some of the most exciting independent cinema around. They put on films encompassing the history of cinema, and from all over the world. “It was a great period; the heyday of independent cinema,” recalls Pat.

The Ritzy became a cultural hub, a mirror to the left-wing politics and radicalism of Brixton at the time. The programme reflected this, with passionate discussions often following films on feminism, LGBT rights, Latin American politics, environmental issues and much more. In fact, the reputation of the cinema became so intertwined with its politics that the general manager Clare Binns – still employed at the Ritzy now – felt compelled to place an ad in the local paper reminding people that not all the films were “left-wing or gay”.

It also seems that strikes at the Ritzy are nothing new. Such was the LGBT element within the Ritzy, that at one point in 1981 Pat discovered that a small clique of their staff had begun to censor parts of films which they saw as homophobic. Dismayed that such action had been taken without consultation, he fired the two main culprits. Within a week there was a picket outside supported by the Socialist Workers’ Party. The cinema opened its doors on the first night of the picket, but very few people came.

With a PR disaster looming, the management decided to stay shut the next day and plan their next move. That was Friday 10th April. On Saturday, the first Brixton riots broke out. The strike was swept away by the rioting, never to be resumed. The Ritzy emerged unscathed, and played a key community role by putting on a massive benefit gig, featuring a fledgling UB40, for all those arrested by the Police. “The riot actually saved the reputation of the Ritzy in many ways.” says Pat.

On the recent pay disputes, Pat understands why the management were reluctant to increase wages, but believes they made a “huge mistake” regardless. “They are living in a completely different world to the one we operated in. The industry has changed enormously. Still, they never should have got to a point where they were paying below the living wage.”

Asked whether they ever thought about the role of the cinema in the local community while he was running it, and whether they felt the need to tailor their output and activities accordingly, Pat says: “We thought about it a great deal. But our principle motivation was to show films of quality. We ran arthouse film, sometimes to our great detriment. There turned out not to be a great audience for a subtitled black and white Czechoslovak film!”

Pat admits that he found it harder to integrate a programme that would appeal to the local black community, as they excluded Kung-Fu which was considered a big draw for the West Indian crowd. They put on the Black and Third World film festival, and when there was a film with a strong black lead, they tried to show it. “If I’m honest though, it was never enough, and maybe we could have done more,” he concedes.

By the early nineties, although the cinema was still doing well, Pat had tired and was in need of some money. The other partners in the business – his brother and Clare Binns – were also open to a change. Clare in particular was ambitious to take the Ritzy to the next level, so when the opportunity presented itself in the form of a Michael Heseltine-led scheme to provide funding to local councils for regeneration, they made their move and began pitching to the independent cinema circuit for potential investors.

Peter Buckingham, a former Brixton resident and the manager of arthouse distribution company Oasis, immediately saw the potential. Buckingham convinced the owner of Oasis, Chris Blackwell (the British-Jamaican businessman and founder of one of the great independent music labels – Island Records) to put up the necessary funding and the so the modern Ritzy was born.

Peter Buckingham’s vision for the next phase in the cinema’s development was simple. He believed arthouse cinema needed to be upgraded – more screens, better services and more facilities. He also had great respect for what Pat and his team had done and saw it as his mission to preserve a cinema which was politically conscious and connected to the community. When I meet Peter at the Ritzy for our interview, he is visibly moved at returning to a place which for a long time was his life, and takes a moment to take in the new and much changed surroundings.

Under Peter’s watch, the Ritzy formally became ‘the Ritzy’, and in 1994 began a full modernisation. To the existing cinema, Oasis added four new screens, the current restored facade and signage mimicking the original style of the Electric Pavilion, a bar and a café. Peter describes it as his “proudest achievement.” A new cinema for a changing Brixton.

Peter explains that this was a brave project to fund at the time. Britain was coming out of the Conservative era and Brixton’s image was still stained by riots and deprivation. Fixing the inner cities was not high on the agenda for many in power.

Peter credits Heather Rabbatts CBE, the chief at an embattled Lambeth Council at the time, with providing vital support to get the regeneration funded. “She is an amazing woman. Without her I’m not sure we could have pieced it together,” he says.

Funding secured, there were still all manner of trials and tribulations to contend with in getting the cinema up and running. Peter remembers confronting skinhead looters during the rebuild who had decided to turn squatting laws to their advantage in ransacking the site. A last-minute high court injunction was eventually faxed and handed to the Police, who finally intervened.

Where the 1981 riots had worked to the Ritzy’s favour in some ways, here they put a major spanner in the works. With impeccable timing, just two weeks after officially throwing open its doors, and with Peter having declared Brixton renewed and rehabilitated to all concerned, the 1995 riots kicked off. With the world’s press camped on Windrush Square, Peter wondered what he’d done to anger the cinema gods. That minor hiccup aside though, the cinema was a “pretty immediate hit”.

On the subject of the Ritzy’s role in the local community, Peter says he’s never encountered a cinema which is as challenging in terms of meeting the hopes and expectations of locals. “There are considerable sensitivities of how people project onto the cinema. We had to deal with complaints that we were too white, too arthouse.

“We were very conscious about rooting the programming in the local area and reaching out to local business owners and stakeholders though. If you don’t do that it’s just another cinema, another chain,” says Peter. He’s reluctant to say whether he thinks it’s actually possible to have a cinema run by a major PLC like Cineworld which upholds those values.

Peter says that it was always his belief that the cinema really belonged to the community, rather than the owners. “I had the feeling that if you played it really wrong, then bad things could happen. You’d get targeted in a riot, or staff would rebel.” He thinks the current management may have taken their eye off the ball on that count. “Maybe it’s the physical location. People have emotional connections to public buildings.”

Skip to 2015, and the Ritzy has continued to evolve – an ever-more polished cinema for new Brixton. Nevertheless, there are still few better places to catch a film. It remains a much-loved old institution, as much a community hub as it ever was, serving up a wonderful blend of mainstream, arthouse and live events.

Let’s hope it stays true to its roots for a long time to come.

(Thanks to Brixton Society and Gavin Freeborn for images)

[…] If you love the Ritzy too, read the full article here. […]

I remember a packed house in the main cinema to raise money for the Miners, during the Great Miners Strike in 1984/85; momentus times when Welsh Miners “camped” in Brixton and the Red Flag flew from the Town Hall.

And you forget to mention that the Ritzy hosted the UK premiere of The Harder They Come in 1973, with English subtitles.

You forgot to add that its frontage beautifully restored in the 1995 rebuild will be dwarfed and ruined if the giant LED ad screen is erected right opposite on the Prince of Wales corner,