When Brixton’s Remploy factory closed in 2008, its workers were told they would be better off in mainstream employment. Emily Churchill meets two who fear they will never work again.

Ray Dearman is dreading Christmas. Although he is a hard-working volunteer for a mental health charity, he hasn’t received a pay cheque for over five years, and is struggling to get by.

“Christmas has to be cancelled because I just can’t afford it,” says the 54-year-old.

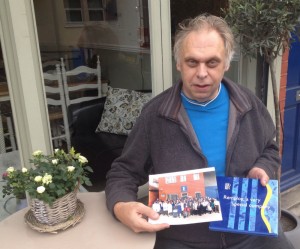

Ray, who has a learning disability, was one of 47 people to lose their jobs when the Remploy factory in Effra Road, Brixton, shut its doors in 2008. It was one of 29 state-subsidised plants, which employed disabled people across the country, to close that year.

At the time, several disability charities backed the closures, saying disabled people were more likely to lead fulfilling lives if they worked in an “inclusive environment”. But others questioned whether this was a realistic prospect for most disabled people – including the London Assembly, which argued that in deprived areas like Brixton, it would be “extremely difficult” for former Remploy workers to find jobs.

If the debate sounds familiar, it’s because it was resurrected last year when, to the outrage of many disability rights campaigners, the coalition government shut down dozens more Remploy plants.

Whether the promises of finding mainstream work have been fulfilled is debatable at best. In April, Minister for Disabled People Esther McVey said more than half of former workers on the government’s support programme were in employment or training. But this only amounted to 308 people in paid work of over 16 hours per week – less than a fifth of the 1,600 who lost their jobs.

Desperate to work

Five and a half years on, Ray Dearman is still looking. A forklift driver at the Effra Road factory for 14 years, he suffered a mental breakdown after it closed.

“It was really good, you felt part of a team,” he says of Remploy life.

“But in the outside world Remploy people don’t stand a chance.”

Due to his mental state, Ray was initially granted incapacity benefit, but was later deemed fit to work and moved onto Jobseekers’ Allowance.

His palpable pride at what he and his colleagues achieved at Brixton Remploy is in stark contrast to his description of life on the dole, which, at 54, makes him feel like he has “no future”.

Ray doesn’t know for certain why the job hunt has been so hard, although he feels his physical health and lack of computer skills are barriers. And while it is illegal not to give someone a job because they are disabled, it’s not hard to imagine that in the current climate, employers sifting through stacks of CVs might not be as open-minded as they should to someone with a work history at Remploy.

One thing’s for certain, and that is Ray desperately wants to work. If his breakdown had a silver lining, it was that it brought him through the doors of mental health support programme Wandsworth Your Way, where he has been volunteering for the past three years.

“I’m really proud of what I’m doing at Wandsworth Your Way,” he says, describing the programme “saving people’s lives”.

But it doesn’t pay the bills, and Ray, who lives with his elderly mother, is worried what will happen if his Jobseekers’ Allowance is cut as conditions on benefits get tighter.

Even if he does manage to find a job before then, he is not sure that mainstream work is the best option for him. Remembering how he ‘got his leg pulled’ at a previous job at London Transport, he remarks that at places like Remploy, “you’re not taken the rise out of”.

‘They don’t want to employ you’

Ray Ludford worked alongside Ray Dearman for seven years as a factory operative at Effra Road. But unlike Dearman, the father of two, who has cerebral palsy, says he would prefer to work in a mainstream setting if he could.

“If it was a job I could physically do, I would go for it,” he says.

But it’s not an option the 56-year-old feels is open to him. Despite applying for thousands of jobs over the past five and a half years, he hasn’t had a single job interview since he left the factory floor.

“I do [apply for jobs] but there isn’t a lot of point,” he says.

“When they get your application form, the first thing they look at is your age, and they chuck it in the bin.”

As far as Ray is concerned, arguing that disabled people should work in a mainstream environment is academic, because employers aren’t prepared to take them on.

“The argument for closure [of Remploy factories] was complete nonsense,” he says. “The argument was if you spend that money elsewhere you’ll create more jobs. But the problem for disabled people is employers don’t want to employ you.”

“Because from an employer’s point of view, if an able-bodied person can do something faster than you can, from a competitive point of view, they’re always going to employ that person. And that’s true of most disabled people.”

However, Richard Farnos from Lambeth Resolve believes the blockage lies primarily not with disabled people’s capacities, but with employers who suffer from prejudice and a lack of awareness of the support that is available for disabled people in work.

“If people are giving right equipment and support they can perform as well as able-bodied colleagues in lots of roles but disabled people are discriminated against, and bringing a discrimination case is very difficult,” he says.

Any job better than no job

The debate over how the state should support disabled workers will no doubt rage fiercely for years to come. But for Dearman and Ludford, it’s clear that having a job at all is more important than where that job is.

As Ray Ludford puts it: “If you said to [any disabled person] ‘would you rather work for a Remploy-type organisation, where most of the workers round you are disabled, or would you prefer to be on benefits?’, they’d say ‘don’t be silly, we’d prefer to be in work’.”

Yes, there are no doubt good reasons to question the ‘sheltered’ employment model. But for these two men, the closure of Brixton Remploy simply meant the beginning of almost six years without work. Which feels hard to defend, especially with Christmas coming up.