Hill Mead school on the Moorland/Somerleyton estate organised its first conference in school hours yesterday. It discussed the school’s important two-year research project. Alan Slingsby reports

Year 1 children from Brixton’s Hill Mead school setting off on a trip to Margate tomorrow (15 July) as part of a project on sharks, will probably be blissfully unaware that they are key players in a two-year research project that goes to the heart of many of the current fierce debates on education.

But, as a conference at the school heard yesterday, they appreciate the way it is encouraging their teachers to teach.

One participant told the audience of teachers and education experts about a Hill Mead pupil who was asked by a visiting dignitary what she liked about the school. “The teachers,” she replied. “The teachers understand.”

And understanding is central to the Hill Mead project.

At a time when many schools are turning to computerised tests and statistical analysis that reduce pupils and their work to numbers, Hill Mead has been testing out a completely different approach.

More than one conference participant called it “slow learning” in a nod to the slow cooking movement. “There are no instant answers,” said one.

Deputy headteacher Becky Lawrence said the idea was to focus less on external assessment of pupils and more on learning itself – encouraging both pupils and teachers to reflect on and understand how they learn.

She gave the example of a year 2 boy who was struggling academically and found it hard to talk about his school work. He was one of a group taking part in a project that combined, among other things, religion and modelling.

She gave the example of a year 2 boy who was struggling academically and found it hard to talk about his school work. He was one of a group taking part in a project that combined, among other things, religion and modelling.

The group made models of an ancient Egyptian cat sculpture found in a tomb.

His model was the only one where the cat was not sitting up. When the teacher asked why, he explained it was praying. He had understood what the project was about and used his intelligence and creativity to reflect this in his work.

After this, he found his voice.

“I’m pretty sure that was because of the way we approach learning,” said Lawrence. “We were looking at the boy through a different lens.”

She added: “We haven’t done anything new, but we have shifted the perspective. And we, the teachers, are learning all the time too.”

Education consultant Sue Ellis, who, with her colleague Dr Myra Barrs, has been part of the two-year project, said that Hill Mead pupils “are aware that teachers value what they think”.

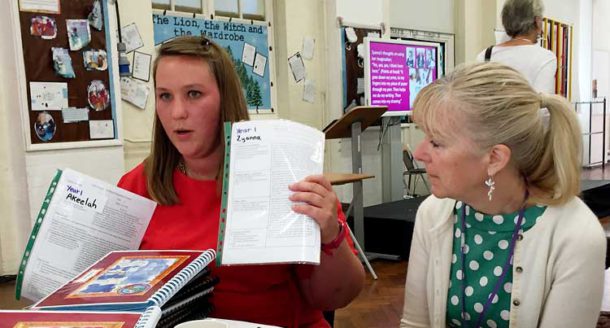

Behind that simple example are many hours, days and months of discussion and research and hundreds of sheets of paper.

And Hill Mead’s project is taking place in the middle of repeated government “reforms” and fiddling with how children and schools are assessed – what education consultant Dr Myra Barrs described as “a spreading disaster area for 20 years”.

That disaster has seen the growth of school “league tables” and revolts by parents and teachers against too frequent testing of children who are too young.

Hill Mead headteacher Richard West said that the school was not interested in assessing pupils using systems that produce numbers and little else.

Each Hill Mead pupil has individual, written learning targets, not generated by machines and not “ticked off on a grid”. They are based “only on our own knowledge” and ”written on a plain piece of paper”.

Under the glaring eyes of a giant red and gold papier maché dragon hanging from the ceiling, teachers and education professionals from across London discussed the Hill Mead project and afterwards toured classrooms to see its approach to learning in action.

Under the glaring eyes of a giant red and gold papier maché dragon hanging from the ceiling, teachers and education professionals from across London discussed the Hill Mead project and afterwards toured classrooms to see its approach to learning in action.

They heard Dr Barrs, who has worked in New York and California as well as London, describe working with the school on the project as “one of the best experiences of my professional life. It was hard, but it was really, really worth it.”

Richard West reminded participants that Hill Mead is the proud owner of an “outstanding” rating from the official school inspection body, Ofsted.

He added that many teachers saw a visit by Ofsted inspectors as “oppositional”, but, usually, it was not, he said.

You can find out more about the project here.

And, just in case you thought a trip to Margate might have less to do with sharks than ice cream and a paddle – and who would begrudge a six-year-old that – have a look at this.

Council warns of 20% budget cut

Last night’s full meeting of Lambeth council backed a call from Councillor Jane Edbrooke, council cabinet member for education, for central government to drop its drive to turn all schools into “academies” that are independent of their local authorities.

She pointed out that, in its annual report, Ofsted had said that Lambeth had “nothing but good and outstanding secondary schools”, while 94% of its primary schools were “good” or “outstanding”.

Councillors agreed that these achievements would be undermined by the government’s academies drive and “ill-thought through changes to funding mechanisms which will see a 20% cut in Lambeth’s education budget”.

But life *is* ticking boxes.